Mendocino is more beautiful than I expected. The ride there is equally lovely.

Mendocino is more beautiful than I expected. The ride there is equally lovely.

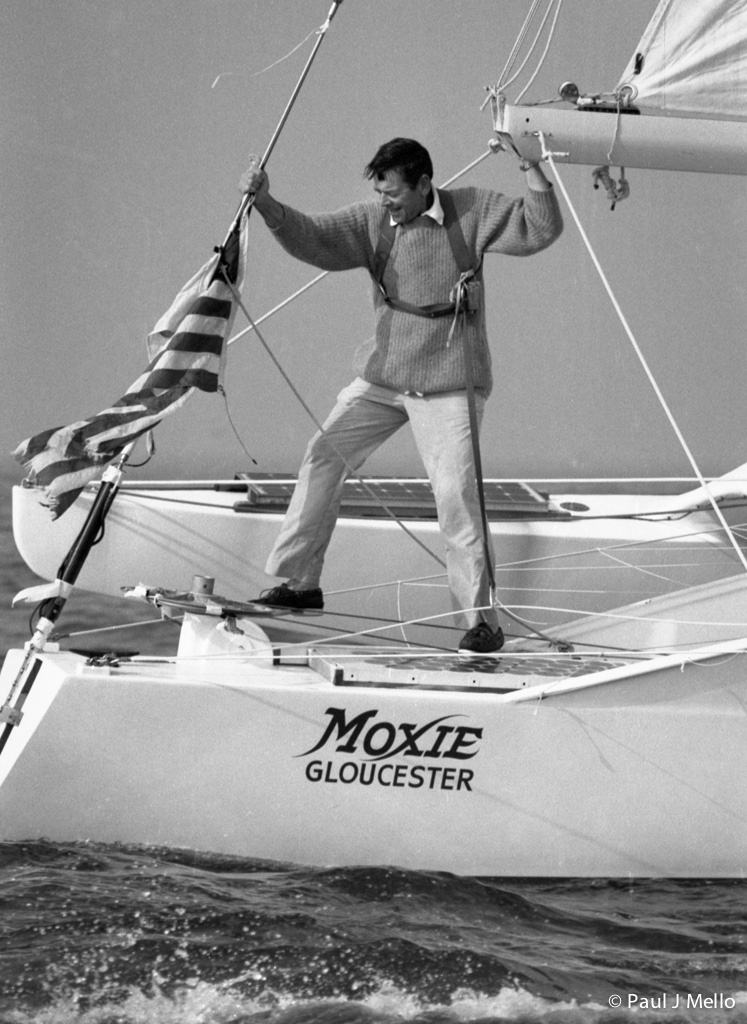

I first met Dick Newick at the finish of the 1980 OSTAR in which a “senior” Phil Weld won the singlehanded race from Plymouth UK to to Newport RI in Moxie his Newick designed trimaran. I will confess I thought the boats did not look very elegant. But that an older man could beat all the hotshots of the time must have been a wonderful feeling for Dick Newick.

The Following Article

Is Provided

Courtesy of Professional Boatbuilder magazine

&

Steven Callahan

Articles are presented exactly as they first appeared in Professional Boatbuilder © Professional Boatbuilder & Steven Callahan; All Rights Reserved

Permissions to reprint or otherwise reuse is required.

For permissions, please contact the author; email at: steve@stevencallahan.net

Or click on the email address on the bottom of the Home Page.

To return to Steven Callahan’s Home Page, click below:

http://www.stevencallahan.net/schome.html

To return to Steven Callahan’s ProBoat Articles Page,

which includes links to a number of articles on leading designers, click: http://www.stevencallahan.net/proboat.html

To return to Steven Callahan’s Publications Page which includes links to both articles and books, click: http://www.stevencallahan.net/publications.html

OR

You can go directly to the Articles Page,

which links to both the Professional Boatbuilder Articles Page

and other sites containing articles by Steven Callahan,

by clicking: http://www.stevencallahan.net/articles.html

Or

You can go directly to the Books Page,

which links to books by Steven Callahan and his associates,

plus descriptions and links to books recommended by Steven Callahan, by clicking: http://www.stevencallahan.net/books.html

The magazine for those working in design, construction, and repair

NUMBER 122 DECEMBER/JANUARY 2010

$5.95 U.S.

N EWICK MULTIHULLS LONG-TERM LAYUP NICHE-MARKET DIESELS WEB-ASSISTED MANUFACTURING

1 Professional BoatBuilder

122 PROFESSIONAL BOATBUILDER Newick Multihulls • Long-Term Layup • Niche-Market Diesels • Web-Assisted Manufacturing DECEMBER/JANUARY 2010

Intuitive Dynamics

The venerable Dick Newick, a pioneer in sailing multihulls, continues to deliver designs whose simplicity and grace, even at rest, are evocative of seabirds. His fast, safe, ocean-proven multihulls can truly be said to have been “ahead of their time.”

by Steve Callahan With circumnavigating sailboat races now capturing more press than the Super Bowl; with mul- tihull speedsters as plastered with multinational corporate logos as any Daytona 500 racecar; with multihull workboats proliferating like eels; and now, with 90′ (27.4m) multihulls lined up to race for the America’s Cup—it’s hard to recall just how reviled multihulls were as recently

as the 1980s.

Like most art that has reconfigured

the future, designer Richard “Dick” Newick’s creations threatened some as much as they enlightened others.

At times, his trimarans’ simplicity, structural reliability, and astounding speed seemed like grenades tossed into yacht clubs. One sailing maga- zine editorial, titled “Unsafe on Any Sea,” took all multihulls to task, and featured a photo of Newick’s Trice — despite the fact she never suffered a structural failure or other mishap until destroyed by hurricane Hugo in 1989. Indeed, many of the concepts and design features that arose from Newick’s explorations have so shaped the norm of all sailboats over time, that we now might wonder why there was such a fuss in the first place.

|

Above—The Newick-designed Ocean Surfer, a 40′ (12.1m) solo racer skip- pered by Mark Rudiger, placed second in class in the 1988 OSTAR single- handed transatlantic race, completing the crossing in 18 days. She was the first boat built in the U.S. with Durakore, a then-new material sandwiching end- grain balsa between mahogany skins to be sheathed with fiberglass and epoxy. The boat’s maststep slides to leeward to heel the rig—itself another Newick first. |

40 Professional BoatBuilder

COURteSy DICk NewICk

Left—Newick’s first trimaran, Trine, was designed and built by him for his and wife Pat’s day-charter business in the Caribbean. Trine remains active in that trade, under new owners, nearly 50 years later. The cockpit accommodates six guests comfortably; there’s a berth and WC forward. Construction is plywood, with cedar strip below the waterline, all glass-sheathed. Right—Lark, a 24′ (7.3m) 1962 design, is believed to be the first tri to employ “dagger-foils”—angled daggerboards—in the amas (outriggers). The boat was bought by banker David Rockefeller for use at his St. Barth’s residence. Newick had not yet developed the signature sculptural shaping of his tris, which better integrated the amas and vaka (main hull). Note the Herreshoff and Alden sailing yachts in near background at left, in Christiansted Harbor.

From an early age, Newick discov- Holland, Germany, and Denmark,

ered the joy of crossing water in slim, lightweight craft. He embraced the simple life that required keeping a vessel light, and the close touch with the sea it provides, leading him to explore cruising frontiers long before their value became obvious.

Newick’s first boat was a kayak he built at age 10 with his father and brothers in the family’s garage in Ruth- erford, New Jersey. “I was a skinny kid who was lousy at team sports,” he recalls. His father, a skilled craftsman, rightly thought the project would also build young Dick’s self-confidence. At 11, Newick built another kayak with family. At 12 he thought, “I can do this,” so designed and built two, one for a friend. At 14, he sold his first plans to a schoolmate for five bucks.

In the early 1950s—after a hitch in the U.S. Navy, after earning a college degree, after running a boatshop in eureka, California, and then work- ing with Quakers in Mexico to help prison inmates and schoolchildren— he loaded an 18′ (5.4m) kayak on a ship and headed for postwar europe.

there, Newick cruised 600 miles through the canals of Belgium,

decades before kayaking would become a global middle-class sport.

Newick’s design philosophy is firmly rooted in that trip. He reveled in living simply, sleeping under bridges or in haylofts or a small tent or youth hostels. Sailing a third of the way, paddling a third, and riding on work- ing canal craft a third, he became increasingly conscious of how every pound of gear added drag to the kayak.

wintering over in Denmark, living in a minesweeper’s discarded wheel- house lit by kerosene lamps, Newick fed a woodstove with bits of beached, dead commercial-fishing boats and, he recalls, “learned how to build a strong boat by attacking nearby hulks with an eight-pound [3.6-kg] maul and axe.” Once things thawed, he bought sev- eral Folkboats, the most expensive of them for $2,300, and shipped the sail- boats to San Francisco for resale.

Hitching rides down europe’s coast and across the Atlantic on a variety of watercraft, Newick extended his cruise to 22 months and 10,000 miles through 11 countries. He noted the sparkling performance of Uffa Fox’s Flying Fifteen and other small, fast

|

Dick Newick 30 years ago, cruising the Gulf Stream at the helm of Rogue Wave (see page 46). Now in his 80s, Newick runs his design practice in Sebastopol, California. |

decemBer/January 2010 41

JIM BROwN FRItz HeNLe (BOtH)

english sailboats. He admired the practical arrangements of the numerous working sailing craft he encountered throughout.

Along the way, he met surprising numbers of early long-distance cruis- ers and singlehanded sailors follow- ing the lead of tom Crichton, “whose book Sailboat Tramp had helped to start my wanderings,” Newick wrote in a series of articles for The Rudder magazine in 1956. Crichton voyaged from Sweden to Israel in a 25-footer (7.6m).

Notably, many of the sailors Newick met also sailed quite small craft. Arne Christiansen, for example, sailed a 23-footer (7m); John Goodwin’s boat in Barbados was 25′ ; and tom Follett sailed a 23-footer to the United States from the United kingdom, accom- panied by Newick for the last 1,200 miles. the size of the boat seemed to be in inverse proportion to the adventure one could capture with it. “New friendships and ideas could not be numbered, much less evaluated, in ordinary terms,” Newick wrote. And all for a couple of thousand dollars.

After joining Follett on his passage to the mainland, Newick headed back to the Caribbean for St. Croix, in the Virgin Islands, where he met and sub- sequently married Pat, whom he now refers to affectionately as “that girl I used to go with.” together they built a day-charter business over the next 17 years with a native sloop and, signifi- cantly, multihulls Newick designed and built. “I had only one design customer, and he was easy to please,” he recalls, though others soon followed.

Crossing the Atlantic in a narrow 40′ (12.1m) monohull racer with long over- hangs had the effect of literally rolling catamarans into Dick’s considerations. So he built the 40′ catamaran Ay-Ay for $8,000, which proved to be an ideal charter platform for the next 42 years,

16 of them under Newick’s ownership. Soon, though, he turned to trimarans.

Caribbean-based designer-builder Peter Spronk (see Professional Boat- Builder No. 119, page 30) worked with Newick and went on to create some of the world’s most beautiful catamarans, primarily because, as Newick observes, Spronk never tried to cram too much accommodation and other “modern inconveniences” into them. Spronk’s low wing-decks slammed a good deal, though. Newick’s trimarans seemed more complex, provided a stiffer staying platform for the rig, greater wing clearance, and better maneuverability and upwind performance. Newick started out with 24′ and 32′ (7.3m and 9.7m) daysailers, then created the 36′, 2-ton (10.9m, 1,814-kg) Trice, a boat that signaled future developments.

So-called “first generation” mod- ern multihulls, such as Piver-designed trimarans, had capitalized on rela- tively new plywood; the results, how- ever, were boxy cabins, hard angles, and flat-sided V hulls. By contrast, Newick’s strip-planked bottoms and tortured plywood yielded hullforms with more curved V-sections. Also, the rounded edges on the bottoms of his connective platforms began to suggest gull wings. In addition, Newick raised the amas (known then as “floats” or “outriggers”) until they danced lightly on the sea with the boat at rest. when sailing, the weather hull lifted well clear of the water, reducing drag. the centers of volume on the amas also moved forward, in order to counteract the real direction of sail forces, espe- cially downwind.

Subsequently, designers would strug- gle for decades to really appreciate the huge loads on a multihull—owing to

its enormous righting moment and power to carry sail. But Newick him- self didn’t hesitate to employ substan- tial beam structures that made up a large percentage of the boat’s weight.

At a time when conventional boat design was substantially oriented around stock hydrostatic formulas, Newick established himself as a wiz- ard of intuitive dynamics.

So in 1964 and 1965 he set off on Trice, with her spartan accommoda- tions, and sailed round-trips of 3,200 miles to New england. “Newick gave the impression it was all in a day’s work,” later wrote designer Robert Harris. eager for a performance yard- stick, Newick sailed Trice alongside the 1964 Newport–Bermuda Race, with a crew of four. She was beaten only by the big monohull racers in the fleet, Niña and Stormvogel.

to the small cadre of multihull affi- cionados, Dick Newick was already regarded as an innovative designer, builder, and sailor. But it took the 1968 Observer Singlehanded trans- atlantic Race, or OStAR—at the time the premier event for singlehanded sailors and their no-holds-barred boats—to telegraph Newick’s talent around the world.

In 1968, it was impossible to put the Newick-designed Cheers into context, except that she’d finished third. She looked extracted from a sci-fi novel. Curvaceous hulls and the

N

ewick’s structurally reliable

boats, unrestrained by conven- tional hull speeds, were racing and winning—routinely, locally. But, says Newick, “I was living in the boon- docks and had no real competition. I wanted to see how my boats stacked up against the big boys.”

|

Cheers, a radical design in its day (1968), shown dockside in Port Saint Louis in the south of France, in August 2008. The 40′ (12.1m) boat, which Newick calls an “Atlantic proa,” was raced transatlantic by skipper Tom Follett. He became the first American to finish an OSTAR, and Cheers the first multihull ever to place. Cheers, recently rebuilt by her French owners, has been designated a “historical monument” by the multihull- conscious French government. |

42 Professional BoatBuilder

RON GIVeN

COURteSy DICk NewICk

occasional rounded form on deck OStAR, and Cheers the first multihull

In 1972, Newick would offer similar innovation in a 46′ (14m) trimaran called Three Cheers, also to be raced by Follett and also commissioned by Cheers’ original owners, Jim and “tootie” Morris—the first in a series of multiple-boat clients. Freed of con- ventional forms, thanks to laminated wood veneers (and later, compos- ites), Newick created an entirely new aesthetic.

A “wing aka” spanned Three Cheers’ now-trademark Newick canoe hulls; with ends aimed upward, the vaka bow was elegantly flared to shed water. Previously, even other multihulls had largely clung to a traditional monohull for- mat, wearing angular cabin trunks spread onto flat-topped wing decks; or installed trussed or cantilevered beams bolted to amas.

By contrast, Newick’s aka smoothly bent its wings over the whole struc- ture. He had effectively eliminated angles where stresses might concen- trate, and added generous fairings to corner joints forward. In so doing, the deck and wing-bottom became widely separated webs for a large, super-stiff, yet lightweight beam spanning a third of the boat’s length, integrating and stiffening the entire boat’s structure while providing headroom and vol- ume below. though primarily stream- lined for reducing wave resistance, the wing aka also reduced wind resistance. Three Cheers’ wing aka

might beautify other boats, but on Cheers there was nary a straight line or angle in sight. two needle-thin 40′ canoe hulls, with spoon bows and rounded decks, were spanned by highly arched beams. On the weather hull, a reserve-buoyancy pod bulged from the streamlined cabintop. Amidships and to leeward, the ama’s freeboard rested just inches above the water. the boat didn’t tack; she changed ends, like Pacific proas with which islanders had explored the Pacific basin centuries before euro- peans found the nerve to sail monohulls to the Americas.

Prior to Newick, proas had been nearly forgotten, even in parts of the Pacific, and were virtually unknown to western eyes. Furthermore, his Cheers was abnormal even for a proa. what he referred to as an “Atlantic proa” kept the vaka (main hull), with accommodations, to weather, rather than to leeward as in the Pacific tra- dition, giving her even more stabil- ity per pound than a catamaran of equal beam. She had no keel or cen- terboard as such; instead, there was a pair of dagger-rudders. the crew would lower the aft rudder to steer while swinging the mainsails around on their unstayed masts.

Such a departure from all traditions usually is destined to face scores of fundamental problems. But after get- ting caught aback and knocked down to weather in trials, and then gaining her pod, Cheers went on to be sailed by the capable tom Follett across the Atlantic twice. In an upwind race in conditions so foul that half the fleet retired and two badly conceived tri- marans fell apart, Cheers finished right behind purpose-built 57′ and 50′ (17.3m and 15.2m) monohulls honed to race to weather. Avoiding the worst storms by sailing a course nearly a thousand miles longer, Follett became the first American to finish the

to place.

Newick boats would finish in

the top five in all three of the next OStAR races as well, including a win in 1980, thereby launching not only Newick’s career as a preeminent multihull raceboat designer, but also the golden age of multihulls generally.

“the Cheers project will stand as a perfect example of the sort of thing the OStAR was designed to encour- age. I don’t know which to admire most: the extreme unorthodoxy of the boat’s conception; or the strength and simplicity of her construction; or perhaps her wild good looks; or tom Follett’s impeccable seaman- ship,” wrote Blondie Hasler, famed adventurer and one of the OStAR’s originators.

“Carry substantial liability insurance with you when you take Cheers out for a sail,” wrote Follett the follow- ing winter. “this goes for anything like her at the present (experimental) stage of the design,” he added—a sentiment echoed by Newick, who attributes much of the boat’s success to Follett. though Newick and oth- ers later created other Atlantic proas, none ever achieved Cheers ’ success.

Ironically, this American boat, after decades in a museum, was bought by doctors Vincent and Nélie Besin in France, where she has been made a French national monument. And sails again.

|

The 46′ (14m) Three Cheers, shown leaving St. Croix for the U.K. in 1972 for the start of that year’s OSTAR, in which skipper Tom Follett placed fifth. Newick notes, “The boat was very fast. But before the appearance of electronic autopilots, self-steering was a problem: wind vanes were no good; the apparent wind angle varies too much.” |

decemBer/January 2010 43

presaged a continuing trend toward: monocoque construction, the elimina- tion of point loadings, and streamlin- ing to reduce both wave and wind drag. even today, few designers have exceeded the sublime form of Three Cheers.

Three Cheers clocked 20 knots with a dozen people on board the day of her launch, and later hit up to 27. Follett sailed her to fifth in the OStAR. then Mike McMullen bought her, and helmed her to second in the doublehanded 1974 Round Brit- ain Race, 49 minutes behind the 70′ (21.3m) cat British Oxygen and ahead of Phil weld’s new Newick-designed 60′ (18.2m) tri Gulfstreamer and the French 70′ OStAR winner Manureva (ex–Pen Duick IV), among many other multihull entries.

In 1976, Newick achieved a seem- ingly unreachable pinnacle of racing- multihull design with a humble 31-footer (9.4m): his stock Val-class trimaran. By then, the OStAR had become carnage. Boats broke. Skip- pers disappeared. yet Newick’s diminutive Third Turtle, skippered by Mike Birch, beat three cats, 14 tri- marans, and 106 monohulls, finish- ing right behind Pen Duick VI —a uranium-ballasted monohull maxi, skippered by one of the most success- ful singlehanded sailors and design innovators of all time, eric tabarly, and ahead of the 236′ (71.9m) four- masted schooner Club Med, which

was penalized for outside assistance. Newick’s Val was a conventional oceangoing trimaran in all respects, except she was designed as a day- sailer/camper, with canvas seats and cuddy cabins fore and aft just big enough to squeeze in a berth. Racers walter Greene, placing eighth with a modified Val, and Rory Nugent (46th) reinforced a Val’s capabilities. Until then, efforts to win had concentrated on facilitating the handling of ever- larger craft, leading to the absurdly oversized Club Med. From now on, designers would focus more on effi- ciency. Newick proved that small, simple boats are easier for skippers to handle and drive closer to speed

potential, more often.

Ultimately, over 30 Vals would be

built whose evolved models (includ- ing a recent Val II) would enjoy expanded cabins in wing akas.

the year 1976, however, also ended tragically. en route to that edition of the OStAR, a huge wave capsized Phil weld’s 60′ Gulfstreamer. worse, Mike McMullen’s wife was electro- cuted prior to the start while prepar- ing Three Cheers. And in the race itself, McMullen and the boat disap- peared without a trace, presumed vic- tims of a ship or iceberg collision.

Nevertheless, from those grim cir- cumstances arose another lasting and productive relationship. Phil weld—a blue-blooded publisher, writer, and adventurer—soon employed the Gou-

geon Brothers boatshop (Bay City, Michigan) to build a lighter sister to Gulfstreamer, which weld’s wife, Ann, sug- gested he name Rogue Wave. when size lim- its were imposed for OStAR 1980, weld built a Newick 50-footer named Moxie. At age 65, even though

handicapped by what he called his “geriatric rig” (an in-mast roller-furling mainsail), weld captured the first American win.

For another quarter-century, multihulls would win all offshore shorthanded events in which they were allowed to enter.

T

to facilitate construction while generating beautifully balanced hull shapes, Newick began drawing boats using a “master curve” body- section pattern. Moving a point on the curve along a reference diagonal or waterline, he would join sheer to fairbody at each station. By exploit- ing this technique, he could lay up the amas for Gulfstreamer in the main hull mold, and for a later boat, generate all hull parts by means of a half-hull mold.

years later, multihull builder- designer Jim Brown would be inspired by Newick’s master curve system to develop Brown’s Constant Camber method of cold-molded con- struction, which allows builders to stack-cut veneers, rather than spiling them individually. Subsequently, Brown would follow Newick’s lead of employing variable curves athwart- ships to create more sophisticated “Camberwood” molds that still allow builders to efficiently cold-mold hulls with fine bows, but with fuller hull shapes and transom sterns.

“keep it simple, keep it light,” Newick advises. “you have to be pretty sure what you’ve drawn is going to work, to have faith in the original concept and math, but don’t get beguiled by thinking: ‘If this fails, the whole thing is going to fall apart, so I’ll just make it 10% heavier.’ Beginners think: ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, or maybe my designer doesn’t know what he’s doing, so I should make it stronger.’ Before

o discipline the theoretical with

the workable, Newick tried to balance his time: a third of it sail- ing, a third in the shop, and a third at the drafting board. this approach led him to innovations in construc- tion that complemented those in design. His shapes were far from easy to build, but conceptually, the extra effort to build the basic package was well worth the reduction in com- plex and expensive gear and boat size that were otherwise required to achieve speed.

|

Dick and Pat Newick’s own cruising boat, the 51′ (15.5m) Pat’s, was launched in the late 1980s and is now in Europe under new owner- ship. Auxiliary power is |

44 Professional BoatBuilder

COURteSy DICk NewICk

|

One of the original 36′ (10.9m) racer- cruisers built to Newick’s Echo model, shown racing in the New Zealand Coastal Classic. According to their designer, several of these boats were owner-built in that country; one, professionally built. Newick’s comment on this photo: “We like to sail to windward. In warm weather.” |

you know it, the whole boat is 10% heavier—and not a success.”

with Newick boats formalized in style and consistently winning races worldwide, other designers would naturally push the envelope and explore new concepts to win. Says Newick, “Sitting with some of the world’s best designers looking at my boats, I thought I could see inside their heads: ‘How can I beat this guy’s boat?’ Lo and behold, they’d come out a year later with something a half-ton lighter with 20 square meters [215 sq ft] more sail, and more beam to carry the sail. If you start with my conserva- tive design, you might pull off that iteration once, but then somebody else will try to do it again. Neptune and Aeolus are drinking buddies up in heaven, and they look down and say, ‘Let’s teach that S.O.B. a lesson.’ the world’s oceans are scattered with lessons.”

Just as monohulls have become more specialized as pure racers or cruisers since the early 1980s, so have multihulls. ever more highly engi- neered, wider and more powerful

racers are designed and driven to the very edge. you win, or you crash and burn—a philosophy engendered by what became a fully professional, high-stakes, mostly ocean-racing game in the late 1980s.

N

since moved away from these amas because they require speed to work properly.

to keep the noses up at slower speeds, especially downwind when hit with a gust, he’s reverted to fuller amas with almond-shaped sections. early on, he also employed wing masts, and even tried a canting rig on the 1988 OStAR racer Ocean Surfer. In recent years he’s put revolving unstayed rigs on cruisers like White Wings and Damfino. Following hull- design trends from the up-and-coming Nigel Irens, Adrian thompson, et al., Newick expanded his boats’ overall beams and ama volumes for his newer racer/cruisers like Echo II and Traveler (his personal favorite, not to be confused with Traveller, the first of that model). Ama decks also became routinely rounded to facilitate reemergence when nosing through a wave. though the first Traveller ’s amas are notably flat in profile, Newick typically chooses more rocker and easier sections than are found in today’s Open-class multihull racers, to provide a softer ride in waves and more rounded performance.

ewick never stopped innovat-

ing and adapting—within lim- its. In the early 1980s, in his amas near the forward beam, he employed asymmetrical daggerboards (dagger- foils), canted to provide dynamic lift and more stability with the boat at speed, a feature that eventually became the norm in racing trima- rans. He later introduced “new moon” amas, with convex outboard sides to produce similar dynamic lift, but has

|

The 51′ (15.5m) Traveller is a Corecell/ E-glass/epoxy wing-mast sloop built in Brisbane, Australia, in 2003, and cur- rently based in Auckland, New Zealand. The owner, an experienced transatlantic sailor, cruises Polynesia shorthanded; 300+ mile days are common. A sister- ship won the doublehanded Round Britain & Ireland Race, in 2006. |

decemBer/January 2010 45

COURteSy ANDRew BARtHOLOMew

teRRy FONG

The 60′ (18.2m) Rogue Wave, designed for ocean racer Phil Weld and built by Gougeon Brothers in 1978. Weld was the first American to win the OSTAR (in a smaller Newick tri). Eric Tabarly, the famed French racer, declared Rogue Wave to be the boat he’d like for himself when he “retired.”

As must be evident by now, Newick has never been one to follow any pack closely. “I admire the savvy that goes into the newest racing machines, but it’s just not my way of doing things. I’m no longer involved with OStAR, or its recent iterations, because I’m not interested in racing against somebody who’s able to buy first place with an unlimited bud- get. From 1960 into the 1980s, OStAR

was about the only race that allowed all kinds of boats to race together. we could quickly estab- lish what works and what doesn’t. that was a great challenge. I really enjoyed it,” he says. But that was then.

while he respects the engineering prowess and design skills of Irens, Morelli & Melvin, and others, Newick rarely cites other multihull designers as major influences. Instead, he peri- odically rereads The Common Sense of Yacht Design by L. Francis Herreshoff and applauds designer Dave Gerr’s The Nature of Boats, which provided him with essential aid designing

monohulls. He most admires the design work of william Garden, Olin Stephens, Robert Harris, C. Raymond Hunt, and others with distinctive styles and affable characters. He says, “If I had to go to sea and stay out awhile, my favorite boat is Agantyr,” a hefty cruising monohull from MacLear & Harris’s diverse portfolio. “Speed is one thing we can live with- out when we go to sea. you can’t live without accommodation. you can’t live without safety. you don’t need to go 30 knots,” he confesses, adding, “but it’s fun to try.”

every man has his limits, how- ever. even as the racing world has turned toward new kids on the block, Newick’s clients still want to sail fast, but on reliable structures aboard which one can live reasonably well at sea. “the boats I have evolved fall between hot racers and comfy cruis- ers,” he says. “I’m pushing 30 knots with my racers”; a Newick cruiser, on the other hand, “may be a 20-knot design, or even a 15-knot design. Below 15, I get antsy…. On Rogue Wave, if we weren’t doing 15, I was bored.

“I can give you 20 knots and a snug place to eat and sleep, but I can’t give you luxury and performance and low cost at the same time; nobody can” is a realistic axiom he relates to clients.

Rogue Wave’s study plans: the fore-and-aft views strongly suggest Newick’s characteristic seabird-like shapes. 46 Professional BoatBuilder

DICk NewICk

COURteSy DICk NewICk

that is, you can have a fast, inexpensive boat with limited accommodation; a roomy, fast boat that is expensive; or an inexpensive, roomy boat that is comparatively slow.

“Forty years ago when I was start- ing out with multihulls, we finished an hour or two ahead of big, fancy, well-sailed monohulls in ocean races,” he recalls. Right now, the more com- petitive “60′ [18.2m], twin-rudder, canting-keel, daggerboard monohulls are fine if you want to go fast, but they’re impossible to live aboard.” In contrast, Naga, a stock 38′ (11.5m) Native-model design of Newick’s has not only raced competitively trans- oceanic and throughout the Caribbean, she has also served as a liveaboard

for her owner, Jack Petith, for decades. At this writing, Naga is halfway through a world cruise.

tremolino—a small camp-cruiser that at first utilized Hobie Cat 16 (4.8m) hulls for amas—the Sum- mersault 26 (7.9m), and the Val are models that have all been in limited production, but Newick has not enjoyed the financial success of designers whose work is widely mass- produced. Still, he says, “I do what interests me. Pearson and others have already turned out 300 models of Clorox-bottle sloops. I’m not going to do that. I’d much rather find a small vacuum to fill. I never give a pro- spective client a hard sell, but always question: ‘Do you really want this? I’m

not sure you do.’ I lose design work that way, but I accept that.

“Pat has been telling me for years to stop telling people what they want and give them what they want, or what they think they want. My response is: If they have enough faith in me to hire me, they should lis- ten to me rather than tell me how to do my job, which is to make them happy and safe on the water. If I don’t do that, I’ve failed. My favorite client comes with, say, a one-page list of the attributes he wants in a boat. He may tell me the number of berths, but doesn’t tell me color or go into great detail. then I feel I have a free hand to give him my best work. Ifhetellsmeithastolooklikea

Newick on Vals I & III

Three of the original Val 31′ (9.4m) trimarans that I’d designed were raced in the 1976 OStAR. Mike Birch finished sec- ond in his, behind eric tabarly sail- ing a 73′ (22.2m) monohull. walter Greene placed eighth in his modified Val, and Rory Nugent was 46th (he had equipment problems). Birch’s boat was subsequently sold to Bill

Homewood, who did two more OStARs in her, beating Birch’s 1976 time.

By the year 2000, when the Val III was introduced, it became rare for an unsponsored boat to place well in this type of transoceanic race. (Phil weld’s 50’/ 15.2m Newick- designed trimaran, Moxie, won the 1980 OStAR, the last “amateur” winner.)

Nevertheless, Val III can provide good racing for people without sponsorship or riches of their own.

Construction: strip-planked cedar, or Corecell, glassed both sides. Hull halves joined on the centerline after fabrication over

Continues on page 49

Plans defining the hullforms of a Val III model, at 30′ (9.1m) overall. Newick’s mid-career-and-later vakas and amas appear deceptively simple: their shapes are in fact quite sophisticated. Space here does not permit the full measure of calculations that accompany the lines shown above, in which the designer enumerates separately for the Val III vaka and ama, their displacements (in both fresh and salt water), coefficients (prismatic, block, etc.), ratios (D/L, L/B, etc.), centers (VCG, LCG, etc.), areas (waterplane, lateral plane, etc.), and precise dimensions (including freeboard, and fairbody draft). Newick says of his tris: “High performance is an over-used and often purposely vague advertising term. As used by me, it means the ability to sail safely and comfortably, faster than winds up to about 14 knots, and to achieve over 20 knots in ideal conditions with

a minimum of effort.”

decemBer/January 2010 47

DICk NewICk

certain william Hand motorsailer, I tell him: ‘I’m not your guy.’ Phil weld was the right mix. He was a great guy, the life of the party. He made things happen, and he could afford whatever he wanted—but he didn’t want much.”

Vincent and Nellie Besin are Dick’s most recent dedicated patrons, own- ing Cheers and a Newick trimaran, as well as commissioning Newick to update Cheers by way of a new 56′ (17m) proa with which to sail around the world. “It’s so big it scares me,” Newick admits. Although he is actu- ally keen on the project, sorting out the proa’s technical problems—such as creating reversible rudders so the forward one can be deployed as an efficient foil—with simple solutions remains a daunting assisgnment.

Newick’s aspirations were never really limited to such arcane interests as proas, or even ultimate speed. Pat’s involvement with nutrition and organic foods, decades before it became popular, buttresses Newick’s wider practical concerns about the

planet’s bigger social issues. Dur- ing the first energy crisis in the early 1970s, Dick Newick and Jim Brown, coupled with Phil weld’s bankroll and enthusiasm, focused on working sail, particularly for third world countries. they built SIB (for Small Is Beautiful, after e.F. Schumacher’s seminal book), a working trimaran featuring unstayed masts, Constant Camber hull, and lashed beams. A subsequent design of similar concept sailed to Guyana. Unfortunately, third world politics killed the project, but Brown would go on doing development work in what he more accurately calls the “two- thirds world”; as for Newick, he never forgot the wider needs that boats and creative design might address. “If you have so much money to throw at a problem—like current leading multi- hull racers seem to—and it keeps you out of the bar, then I guess that’s all right. But it’s much better to spend that money developing a cure for cancer or mass-produced electric automobiles,” he says, referring to a design of his own he submitted to Ford. “we desperately need a 35-mph,

two-person car for $5,000.”

As for what people want in boats

coming out of the current recession, he says, “they’ll be cheap and because of that, they’ll be simple.” He designed a slim monohull powerboat for the original owner of Traveler, and now has a model for a powercat runabout, which he estimates will weigh 600 lbs (272 kg) and do 15 knots with four people on board, driven by just a 20-hp (15-kw) outboard. [See “Design Challenge,” page 24 in this issue —Ed.]

Newick’s boats of all types will inevitably remain platforms with which sailors can approach becoming sea creatures in flight, as integrated as nature and machine can get.

Looking back, Newick says, “there’s not much I regret doing. what I regret is not doing some things, not following through. that’s one of my biggest mistakes: I’ve tried something and moved on before per- fecting what was viable because there hasn’t been anyone else’s R&D bud- get to allow it.” Otherwise, “I’m cer- tainly happy to have had the boatshops in eureka, St. Croix, and

48 Professional BoatBuilder

Continues from page 47

temporary frames spaced 24″ /61cm

apart (full-sized patterns are supplied with the plans). Akas and wing mast are similarly built, but with the addi- tion of carbon fiber. to save weight and money, the rudder does not swing up if struck, as in most of my designs; rather, the board has the usual Newick “crash box” to minim- ize damage from grounding or col- lision with a whale. the board will usually be carried deep enough to protect the rudder.

Accommodations: a sheltered steering station, a dry place to sleep with sitting headroom, a single- burner stove, and two buckets.

Electronics: autopilot, GPS, hand- held VHF radio, log, speedometer,

and depthsounder, plus whatever is required by the race rules.

No motor will be carried for rac- ing; a 5-hp (3.7-kw) four-stroke out- board would serve well when not racing. Plans do not include elec- trical or cabin-ventilation details, which will depend on the skipper’s needs. two or more large photo- voltaic panels with either a small wind generator or towed propeller will supply the autopilot and running lights. there is no room for a cap- size escape-hatch; however, sealed compartments would float her high enough to leave a large air bubble in the main hull that would permit a wet exit through the cockpit. No thought has been given to complying

with national or european Union regulations. Buyers should assure themselves that, as racers, they will be able to live with their own bureaucracies.

there are only three sails, all eas- ily handled. the original Vals do 20 knots occasionally. the latest ver- sion will do more than that, and do it more often. After the race, a Val III can daysail several people and cruise one or two spartan types.

Finally, Val III is for sailors who would rather actually race a 30-footer (9.1m) than dream about racing a 60-footer (18.2m). Plans cost $2,000. they are in english units, easily converted to their metric equivalents with an inexpensive calculator.

—Dick Newick

Martha’s Vineyard, where I learned a lot. I’m delighted to have spent two years bumming around europe in lit- tle boats. It was invaluable, especially sailing down the coast with the old

Dane [Asker kure]. And then, 17 years in St. Croix building up the charter business and designing my own boats, and starting to design a few for others—that was a great opportunity.

I think it would be harder for a young guy starting out to do those things now.”

Despite Newick’s near-mythic status, it was with some surprise that any

decemBer/January 2010 49

multihull designer might be in the running for the North American Boat Designers Hall of Fame, jointly spon- sored by westlawn Institute of Marine technology, the Landing School, Mystic Seaport Museum, and the American Boat & yacht Council— especially in only its fourth round. In 2008, Newick joined a very select list of designers: Nathanael G. and L. Francis Herreshoff, Philip Rhodes, John Alden, Olin Stephens,

C. Raymond Hunt, and Jack Hargrave. each judge listed 10 names in order of preference. Dave Gerr, westlawn’s director, then put the lists on a spreadsheet, multiplying points for position on each list. Newick had been on many panelists’ lists since the first selection for 2005, but in 2008, out of 35 nominees, “he ended up toward the top on quite a few lists as well as appearing on quite a few of the other panelists’ lists,” says Gerr,

adding that Newick’s boats “are very distinctive…instantly recognizable as Newick designs. I think the panelists liked the almost austere simplicity of his design approach, which anyone who is a serious designer really appreciates. Dick’s boats are pure and elegant. they work. they are unique. And they are incredibly successful and influential. All these multihulls racing around the world would not exist without the work Dick did.” [For more on this new hall of fame, see PBB No. 113, page 18.]

It seems especially fitting that N.G. Herreshoff and Newick should book- end the 20th century. N.G. Herreshoff accompanied the birth of the techno- logical age with his brilliant catama- ran Amaryllis challenging the yachting establishment; Newick has escorted the multihull into the 21st century, the once radical now embraced.

Newick does not claim this role alone, but acknowledges the sponta- neous evolution of ideas: when many elements of technology and culture are ready, and the ideas are right, then someone will discover them. He notes that elisha Gray and Alexander Gra- ham Bell both applied for patents for telephonic devices on the same day, just as Alfred wallace and Charles Dar- win simultaneously developed theo- ries of natural selection. Perhaps the multihull revolution/evolution would have inevitably happened with- out Piver, Choy, Newick, Crowther, kelsall, Brown, and many others on whose shoulders they stood; but as it happened, they dared to carry and reinvigorate the torch.

Newick, a believer in reincarna- tion, says, “People ask me, ‘where do I get these ideas?’ I can only say, I must have been a Polynesian canoe-builder.”

Perhaps, someday, between the planets there will sail upon the solar winds a daring spacecraft designed by a guy who must have once been… Dick Newick. PBB

About the Author: Steve Callahan has designed and built several boats, authored two books, and written widely in the marine press on modern sailing design, designers, and technologies—including a series of designer profiles for this magazine, reflecting Steve’s special interest in multihulls, a genre in which he’s an accomplished sailor.

NEWPORT BERMUDA RACE PREPARATION SEMINAR

Brewer Pilots Point Marina, Westbrook, CT September 7, 2013

Registration – Coffee and pastries provided

It’s Not as Complicated as it Seems! – Rives Potts and Michael Keyworth

Planning for a Successful Bermuda Race: Entering and qualifying for the race, optimizing the boat, selecting crew, provisioning, sailing fast, having fun, what to expect on arrival, where to stay and keep the boat, getting back to the mainland afterward.

Entering the Race and Navigating the Paperwork – Bjorn Johnson

The entry process and where to turn if you run into problems. The race’s updated website and online entry offers a more intuitive and less stressful means of data submission and tracking your progress through the entry system.

Preparing for Inspection – Michael Keyworth

Inspection doesn’t have to be intimidating and time-consuming. Michael will walk through a typical inspection and point out tips for making it quick and painless.

Race Strategy: Navigation, the Gulf Stream and Weather – Bill Biewenga

Strategy on the 635-mile course: weather scenarios, tactics for using the Gulf Stream, navigating the 300+ miles south of the Stream, and electronic packages for various budgets.

Lunch and Boat Visits – Rives Potts and other skippers

Come on board Carina and other race-ready boats and query their captains and crews. A box lunch will be provided.

Optimizing Your Boat – Rives Potts, Butch Ulmer, Jack Orr, and Jim Teeters

How to make your boat fast and competitive while complying with race requirements (and not breaking the bank). Plus, rating optimization and sail selection.

When the Going Gets Tough – Kit Will and Michael Keyworth

Heavy-weather tactics and skills as well as spares and tools to have aboard – and how to use them in a pinch. Included in the talk will be several practical demonstrations, including cutting standing rigging, using an emergency tiller and controlling flooding.

A Safe Return Trip – Anne and Larry Glenn

The sail home can be as trying as the race down. Many serious safety related incidents occur on the return passage. Anne and Larry will review recent incidents and resources available to owners to help ensure the boat and crew arrive home safely.

Wrap Up

Q&A over Gosling’s new canned and complete Dark & Stormies. Speakers, members of the Bermuda Race Organizing Committee, Race Inspectors, and Brewer staff will be available.

Brewer is the Official Race Preparation Resource for the 2014 Newport Bermuda Race

www.byy.com

OUR SPEAKERS

NEWPORT BERMUDA RACE PREPARATION SEMINAR

Brewer Pilots Point Marina, Westbrook, CT September 7, 2013

Rives Potts – Owner-skipper of the two-time Saint David’s Lighthouse Division winner Carina and President and COO of Brewer Yacht Yard Group. Rives has sailed in 5 America’s Cup campaigns, 15 SORC’s, and multiple transatlantic and transpacific races. Rives is currently serving as Vice Commodore of the New York Yacht Club. (23 Bermuda Races)

Michael Keyworth – Long time Bermuda Race Inspector and General Manager of Brewer Cove Haven Marina (Barrington, RI). Michael has extensive ocean racing experience, including setting a course record in the 1985 Fastnet Race aboard the maxi Nirvana, participation in the SORC, Skagerrak (Norway), Marblehead-Halifax, Miami-Jamaica, and New England Solo-Twin races. (13 Bermuda Races)

Bjorn Johnson – Former Newport Bermuda Race Chief Inspector and Race Chairman, Bjorn has close to 80,000 nm sailing experience, much of it short- and single-handed. He has competed in Newport Bermuda Races, Bermuda One- Two’s, and Marion Bermuda Races. Bjorn is currently serving as the Executive Director of the Offshore Racing Association. (21 Bermuda Races)

Bill Biewenga – Offshore sailor with over 400,000 miles, Bill has raced and delivered boats in every ocean of the world. With 39 trans-Atlantic crossings and more than 60 passages to and from the Caribbean, Bill has been listed multiple times in the Guinness Book of Records for a variety of speed records. As the former owner of a highly regarded weather routing company, he has helped to guide sailors around the world, has published over 400 magazine articles, and written “Weather for Sailors,” a guide to understanding and using weather in sailing. (Number of Bermuda Race Sailed – “I’ve lost track”)

Jack Orr – Jack has been a Sailmaker at North Sails since 1988. During that time, he has been involved in the evolution of sail manufacturing from rolling out cloth on the floor and cutting it by hand, to the latest high tech processes. Jack is an experienced offshore sailor, having sailed in three Bermuda races, two Fastnet races, and a Transatlantic race. (3 Bermuda Races)

Brewer is the Official Race Preparation Resource for the 2014 Newport Bermuda Race

www.byy.com

OUR SPEAKERS (cont’d)

NEWPORT BERMUDA RACE PREPARATION SEMINAR

Brewer Pilots Point Marina, Westbrook, CT September 7, 2013

Butch Ulmer – President, UK Sailmakers NY. Butch is a highly accomplished ocean sailor and racer. His accomplishments include 17 Bermuda Races, 8 Annapolis to Newport Races, 18 SORC’s, and 7 Marblehead to Halifax Races. Butch is a member of the Intercollegiate Sailing Hall of Fame and has won National Championships in the International Tempest and Mobjack classes.

(17 Bermuda Races)

Jim Teeters – Associate Offshore Director at US Sailing, Developer of the Offshore Racing Rule (ORR), and Member of the Technical Committee of the Bermuda Race Organizing Committee. Jim has worked for five separate America’s Cup campaigns as well as for Langan Design Partners and Sparkman and Stephens.

Kit Will – Kit has sailed numerous ocean races, including Bermuda Races, Transpacs, the Middle Sea Race, and the Sydney-Hobart Race. As part of Roy Disney’s Morning Light Project, Kit sailed with some of the world’s top offshore sailors including Mike Sanderson and Stan Honey. Kit has over 35, 000 blue water miles including a 3 month delivery from Sydney to the USVI in 2012.

(4 Bermuda Races)

Anne and Larry Glenn – Anne Glenn is the Chair of the Cruising Club of America Safety at Sea Committee. She and her husband Larry grew up sailing and racing on Western Long Island Sound and have raced various one design classes together during their 50 years of marriage. Currently, they co-own their J- 44 Runaway, which they have cruised and raced extensively with their family. Larry has crossed the Gulf Stream 24 times and Anne 15. (Combined, 22 Bermuda Races and 17 return passages).

Liferaft and Survival Equipment, Inc. will be on hand throughout the day to consult with on safety gear potentially suitable for the race. In addition, LRSE will collect any of your safety gear needing service for transportation back to their shop in Tiverton, RI. All gear will be serviced and returned this fall so it is ready for the 2014 race.

PLEASE NOTE: The Brewer Race Preparation Seminar is not intended as a substitute for the U.S. Sailing sanctioned Safety at Sea events. No credit will be given to attendees of this seminar toward the Safety at Sea requirements.

Brewer is the Official Race Preparation Resource for the 2014 Newport Bermuda Race

JURY CASE AC33 JURY NOTICE JN113

Protocol Article 60 and Oracle Team USA

Protecting the Reputation of the America’s Cup FURTHER DIRECTIONS

DIRECTIONS AS TO HEARING (JURY NOTICE JN102)

1. 2.

3.

On 19th August 2013 the Jury issued Jury Notice JN102.

Jury Notice JN102 stated that on 4th August 2013 the Jury received a report from Richard Slater of Oracle Team USA (OTUSA). Jury Case AC30 followed.

Jury Notice JN102 also stated that the Jury has made an enquiry and two members of the Jury carried out an investigation over the period 13th – 16th August 2013 interviewing 16 members of OTUSA and five employees of America’s Cup Race Management.

HEARING

FURTHER REPORT FROM THE MEASUREMENT COMMITTEE (JURY NOTICE JN112)

6. On 24th August 2013 the Jury issued Jury Notice JN112 attaching a further report from the Measurement Committee. The report referred to the different length of king posts and the depth of engagement of the spigot of the upper main king post fittings on OTUSA AC45 Yachts, boats 4 and 5. The conduct or activity referred to in such report, including racing with such modified equipment will now be a

28th August 2013

part of and included in the hearing to determine if the Competitor OTUSA has breached Article 60.1 of the Protocol.

7. Jury Notice JN112 also included directions that ACEA was required to provide a written submission by 12h00 PDT on 28th August 2013 as to what they consider is the effect of the conduct or activity referred to with reference to Protocol Article 60.1 on ‘the best interests of the America’s Cup, or the sport of sailing’. ACEA filed a submission on 28th August 2013.

INFORMAL DIRECTIONS HEARING

8. An informal directions hearing took place on 28th August 2013 concerning the timing and procedural aspects of the hearing which OTUSA wished to discuss. OTUSA’s Counsel Phil Bowman and Thomas F. Ehman Jr were present.

NEW HEARING DATE

9. To enable the Jury to provide a written Decision following the hearing under Racing Rules of Sailing America’s Cup Edition (RRSAC) Rule 69 in Jury Case AC31, which Decision OTUSA wish to consider before proceeding with the hearing of this Case, the date of hearing is changed to 30th August 2013 commencing at 11h00 at the ACEA Meeting room, Pier 23. It is anticipated the hearing will be completed that day.

COURT REPORTER TRANSCRIPT AND JURY CASE AC31 DECISION

10. The court reporter uncertified rough draft transcript of all of the proceedings to date in Jury Case AC31 and the Decision in AC31 will be made available on a confidential basis to OTUSA, ACEA, ACRM and ETNZ. The parties to Case AC31 have agreed that such transcript be included in this Case and OTUSA have agreed it form a part of the evidence and record in this Case.

ORDERS

CASE AC31 Hearing Transcript

11.1 The court reporter uncertified rough draft transcript of the proceedings in Jury Case AC31 is ordered to remain confidential until further order.

Appearance of Witnesses

11.2 The following witnesses are ordered to be available to give evidence:

Nick Nicholson (Chairman Measurement Committee) Russell Coutts (OTUSA CEO)

Grant Simmer (OTUSA General Manger)

Jimmy Spithill (OTUSA Skipper)

Mark Turner (OTUSA Shore Team Manager) Richard Slater (OTUSA Rules Advisor) Andrew Henderson (Rig Team Manager)

Parties and the Jury are entitled to call other witnesses at the hearing.

David Tillett

JURY: David Tillett (Chairman), John Doerr, Josje Hofland, Graham McKenzie, Bryan Willis.

It is the first time Luc and Felix, 2 1/2 and 2 respectively have met since before they could walk. A re-union oragnized for our 40th wedding anniversary. Within minutes they were fast friends.

Our adventure this summer began on June 25th in Newport, 15 days driving across the country arriving in Los Angeles a month later driving to Sonoma.

The dinner last night in Sebastopol was the gift was hoped for.

On September 7 the America’s Cup action will resume.

America’s Cup: What you may not know about the AC72

By John Longley, 1983 America’s Cup winner

After spending a week in San Francisco and having the opportunity to talk to a number of people who have actually sailed the extraordinary AC72s, I have gathered a bit of AC72 trivia to share…

* If you had an engine to power the hydraulics rather than grinders, you could sail the AC72s with 4 people rather than the crew of 11 they now sail with.

* There is really only one trimmer on board and he controls the wing. The helmsman controls the cant and rake of the board with buttons on a control pad in front of him but only has 3 seconds of stored power before he has to “throw bananas” into the grinding pit i.e. ask for more hydraulic power.

* They have seen 47 knots as the top speed so far but expect to see the 50 knot barrier broken in the Cup match.

* The boats go directly downwind 1.8 times faster than the wind. So if you let a balloon go as you went around the top mark you would easily beat it to the bottom mark.

* There is only 4 degrees difference to the apparent wind from going on the wind to running as deep as you can.

* If you lost the hydraulics while the boats were foiling they would be completely uncontrollable and would most likely capsize.

* It is faster to find the strongest adverse current going downwind because the stronger apparent that is then generated translates into more speed than if you were sailing in slack water. (Warning – this takes a bit to get your head around)

* When sailing downwind you look for the puffs in front of you not behind you.

* It is actually quite dry on the boats, unless you make a mistake and come off the foils, as you are flying a couple of metres above the water. Waves have almost no impact on the boat when foiling.

* In strong wind you carry negative camber at the top of the wing to “reef” or de-power the wing.

* All crew carry personal tackle so they can effectively rappel down the netting if the boat capsizes.

* Gennakers are only used below about 8 knots; the jibs only provide about 3% of the lift up wind.

* The foil on the rudder generates about 800 kg of lift with the rest coming from the center board foil to lift the 7 ton yachts clear of the water.

* The centre board foil’s tip comes out of the water so it effectively works like a governor on an engine i.e. as the board generates too much vertical lift it comes out of the water, the area is thus reduced so it goes back down etc until it finds equilibrium.

MIT researchers have engineered a new rechargeable flow battery that doesn’t rely on expensive membranes to generate and store electricity. The device, they say, may one day enable cheaper, large-scale energy storage.

The palm-sized prototype generates three times as much power per square centimeter as other membraneless systems — a power density that is an order of magnitude higher than that of many lithium-ion batteries and other commercial and experimental energy-storage systems.

The device stores and releases energy in a device that relies on a phenomenon called laminar flow: Two liquids are pumped through a channel, undergoing electrochemical reactions between two electrodes to store or release energy. Under the right conditions, the solutions stream through in parallel, with very little mixing. The flow naturally separates the liquids, without requiring a costly membrane.

The reactants in the battery consist of a liquid bromine solution and hydrogen fuel. The group chose to work with bromine because the chemical is relatively inexpensive and available in large quantities, with more than 243,000 tons produced each year in the United States.

In addition to bromine’s low cost and abundance, the chemical reaction between hydrogen and bromine holds great potential for energy storage. But fuel-cell designs based on hydrogen and bromine have largely had mixed results: Hydrobromic acid tends to eat away at a battery’s membrane, effectively slowing the energy-storing reaction and reducing the battery’s lifetime.

To circumvent these issues, the team landed on a simple solution: Take out the membrane.

“This technology has as much promise as anything else being explored for storage, if not more,” says Cullen Buie, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. “Contrary to previous opinions that membraneless systems are purely academic, this system could potentially have a large practical impact.”

Buie, along with Martin Bazant, a professor of chemical engineering, and William Braff, a graduate student in mechanical engineering, have published their results this week inNature Communications.

“Here, we have a system where performance is just as good as previous systems, and now we don’t have to worry about issues of the membrane,” Bazant says. “This is something that can be a quantum leap in energy-storage technology.”

Possible boost for solar and wind energy

Low-cost energy storage has the potential to foster widespread use of renewable energy, such as solar and wind power. To date, such energy sources have been unreliable: Winds can be capricious, and cloudless days are never guaranteed. With cheap energy-storage technologies, renewable energy might be stored and then distributed via the electric grid at times of peak power demand.

“Energy storage is the key enabling technology for renewables,” Buie says. “Until you can make [energy storage] reliable and affordable, it doesn’t matter how cheap and efficient you can make wind and solar, because our grid can’t handle the intermittency of those renewable technologies.”

By designing a flow battery without a membrane, Buie says the group was able to remove two large barriers to energy storage: cost and performance. Membranes are often the most costly component of a battery, and the most unreliable, as they can corrode with repeated exposure to certain reactants.

Braff built a prototype of a flow battery with a small channel between two electrodes. Through the channel, the group pumped liquid bromine over a graphite cathode and hydrobromic acid under a porous anode. At the same time, the researchers flowed hydrogen gas across the anode. The resulting reactions between hydrogen and bromine produced energy in the form of free electrons that can be discharged or released.

The researchers were also able to reverse the chemical reaction within the channel to capture electrons and store energy — a first for any membraneless design.

In experiments, Braff and his colleagues operated the flow battery at room temperature over a range of flow rates and reactant concentrations. They found that the battery produced a maximum power density of 0.795 watts of stored energy per square centimeter.

More storage, less cost

In addition to conducting experiments, the researchers drew up a mathematical model to describe the chemical reactions in a hydrogen-bromine system. Their predictions from the model agreed with their experimental results — an outcome that Bazant sees as promising for the design of future iterations.

“We have a design tool now that gives us confidence that as we try to scale up this system, we can make rational decisions about what the optimal system dimensions should be,” Bazant says. “We believe we can break records of power density with more engineering guided by the model.”

Yury Gogotsi, a professor of materials science and engineering at Drexel University, says eliminating the membrane is the next step toward scalable, inexpensive energy storage. The group’s design, he says, will help engineers better understand the physics of membraneless systems.

“You cannot have an inexpensive energy-storage system by piling up tens of thousands of individual small cells, like cellphone or computer batteries,” says Gogotsi, who did not contribute to the research. “As any new technology, the laminar flow battery will need time to prove its viability. It’s like a newborn baby — we’ll only know what the technology is good for after a few years.”

According to preliminary projections, Braff and his colleagues estimate that the membraneless flow battery may produce energy costing as little as $100 per kilowatt-hour — a goal that the U.S. Department of Energy has estimated would be economically attractive to utility companies.

“You can do so much to make the grid more efficient if you can get to a cost point like that,” Braff says. “Most systems are easily an order of magnitude higher, and no one’s ever built anything at that price.”

Energy storage has always been the key for any advancement in what we refer to as alternative energy. For autos,computers, cell phones, boats, camping, research,space exploration, homes, buses. Without it we cannot move forward.

Aug. 25, 2013: Inmate firefighters walk along Highway 120 as firefighters continue to battle the Rim Fire near Yosemite National Park, Calif. Fire crews are clearing brush and setting sprinklers to protect two groves of giant sequoias as a massive week-old wildfire rages along the remote northwest edge of Yosemite National Park. (AP)

In this undated photo provided by the U.S. Forest Service, the Rim Fire burns near Yosemite National Park, Calif. (AP Photo)

A massive wildfire racing through the Yosemite wilderness — fueled by high winds — is threatening San Francisco’s fresh water and power supply as well as California’s iconic giant sequoias.

It’s one of several fires statewide being fought by more than 8,000 firefighters across nearly 400 square miles. The fire has consumed approximately 225 square miles of picturesque forests. Officials estimate containment at just 7 percent.

“This fire has continued to pose every challenge that there can be [in] a fire: inaccessible terrain, strong winds, dry conditions,” Daniel Berlant of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection said on Sunday.

The fire continues burning in the remote wilderness area of Yosemite, but park spokesman Tom Medena told the Associated Press it’s edging closer to the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, the source of 85 percent of San Francisco’s famously pure drinking water, as well as power for a number of key city buildings, including the airport. The city has issued assurances that the water quality remains good, but the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission has shut two hydro-electric stations fed by water from the reservoir and cut power to more than 12 miles of lines. The city has been buying $600,000 worth of power on the open market to ensure San Francisco doesn’t go dark.

Meanwhile, park officials are clearing brush and setting sprinklers to protect two groves of giant sequoias. The iconic trees can resist fire, but dry conditions and heavy brush are forcing extra precautions to be taken in the Tuolumne and Merced groves. About three dozen of the giant trees are affected.

“All of the plants and trees in Yosemite are important, but the giant sequoias are incredibly important both for what they are and as symbols of the National Park System,” park spokesman Scott Gediman told The Associated Press on Saturday.

The trees grow naturally only on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and are among the largest and oldest living things on earth.

The Tuolumne and Merced groves are in the north end of the park near Crane Flat. While the Rim Fire is still some distance away, park employees and trail crews are not taking any chances.

Fire officials are using bulldozers to clear contingency lines on the Rim Fire’s north side to protect the towns of Tuolumne City, Ponderosa Hills and Twain Hart. The lines are being cut a mile ahead of the fire in locations where fire officials hope they will help protect the communities should the fire jump containment lines.

Firefighters were hoping to advance on the flames Monday but strong winds, gusting up to 50 mph in some places, were threatening to push the blaze closer to Tuolumne City and nearby communities.

“Winds are increasing, so it’s going to be very challenging,” said Bjorn Frederickson, a spokesman for the U.S. Forest Service.

The Forest Service confirmed late Sunday to KTVU.com  that the fire had burned through the Berkeley Tuolumne Family Campsite, which was owned by the city of Berkeley, Calif., and had been in operation since 1922. Firefighters were unable to immediately assess the damage, and it was not clear if any structures survived. The camp had been evacuated Tuesday and no injuries were reported.

that the fire had burned through the Berkeley Tuolumne Family Campsite, which was owned by the city of Berkeley, Calif., and had been in operation since 1922. Firefighters were unable to immediately assess the damage, and it was not clear if any structures survived. The camp had been evacuated Tuesday and no injuries were reported.

“It’s a very difficult firefight,” Berlant said.

Frederickson added that the fire is slowing down a bit, but still growing.

The high winds and movement of the fire from bone-dry brush on the ground to 100-foot oak and pine treetops have created dire conditions.

“A crown fire is much more difficult to fight,” Berlant told The Associated Press on Sunday. “Our firefighters are on the ground having to spray up.”

The blaze sweeping across steep, rugged river canyons quickly has become one of the biggest in California history, thanks in part to extremely dry conditions caused by a lack of snow and rainfall this year. Investigators are trying to determine how it started Aug. 17, days before lightning storms swept through the region and sparked other, smaller blazes.

The fire is the most critical of a dozen burning across California, officials say. More than 12 helicopters and a half-dozen fixed wing tankers are dropping water and retardant from the air and 2,800 firefighters are on the ground.

Statewide, more than 8,300 firefighters are battling nearly 400 square miles of fires. Many air districts have issued health advisories as smoke settles over Northern California. On Saturday, organizers canceled the 24th annual Lake in the Sky Air Show at Lake Tahoe because of poor visibility.

The U.S. Forest Service says about 4,500 structures are threatened by the Rim Fire. Berlant said 23 structures were destroyed, though officials have not determined whether they were homes or rural outbuildings.

Jessica Sanderson said one of her relatives gained access to the family’s property in Groveland, just 26 miles from the park’s entrance, on Saturday and was able to confirm their vacation cabin had burned to the ground.

The family saw firefighters on a TV news report a day earlier defending the cabin.

“It’s just mind-blowing the way the fire swept through and destroyed it so quickly,” said Sanderson, who’s been monitoring the fire from her home near Tampa Bay, Fla. “The only thing left standing is our barbecue pit.”

At the nearby Black Oak Casino in Tuolumne City on Sunday, the slot machines were quiet as emergency workers took over nearly all of the resort’s 148 hotel rooms.

“The casino is empty,” said casino employee Jessie Dean. “Technically, the casino is open but there’s nobody there.”

As thick smoke portends the fire’s fast approach, the area has been cleared of everyone but locals and emergency workers. Dean lives on the reservation of the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians and left her four children at relatives’ homes in the Central Valley.

But the tourist mecca of Yosemite Valley, the part of the park known around the world for such sights as the Half Dome and El Capitan rock formations and waterfalls, remained open, clear of smoke and free from other signs of the fire that remained about 20 miles away.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

This kind of event has been happening this years all over the west. Remember 19 firefighters died in Arizona. About a year ago we drove through Yosemite on route 120.

It shows how interconnected life is when a wildfire in Yosemite could have such a direct effect on the city of San Francisco.

The win by team new zealand was pretty much a foregone conclusion, I am reluctant to say it but I am not certain what the Italians expected or if they came for the party. I hope they got what they wanted given the price of admission.

Team New Zealand is, I believe, favored to win the America’s Cup. It will be certainly closer than the Louis Vuitton.

Team New Zealand wins the Louis Vuitton Finals 7 to 1; and will meet Oracle September 7 for the best of 17 series.

There was never really any doubt of the outcome; with the exception of breakdowns. The New Zealand team was higher and faster upwind and lower and faster downwind; causing them to jibe fewer times.

See you in September.