A peaceful sunday drive while the volvo ocean race set off for portugal, a 6-7 day race for these boats.

A peaceful sunday drive while the volvo ocean race set off for portugal, a 6-7 day race for these boats.

A Navajo advocacy group has asked a federal judge to halt hydraulic fracking permits in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico, claiming that drilling threatens a historic UNESCO heritage site considered sacred by Navajo, Hopi and Pueblo peoples.

Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment and three other groups have sued the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and US Department of Interior, calling on a federal judge to vacate the 130 fracking permits issued by the BLM and enjoin fracking activity in the Mancos Shale of the San Juan Basin until the BLM adheres to the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act, according to Courthouse News.

The 4,600-square-mile San Juan Basin of New Mexico’s Four Corners region is home to Chaco Culture National Historical Park, which includes the Anasazi ruins and other archeological remains of structures that were among North America’s largest around 1,000 years ago.

Chaco and the surrounding areas, known as the “American cradle of civilization,” are considered a UNESCO World Heritage site. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization calls the area “remarkable for its monumental public and ceremonial buildings and its distinctive architecture – it has an ancient urban ceremonial centre that is unlike anything constructed before or since.”

Chaco is on top of the Mancos Shale, believed to harbor crude oil and natural gas supplies. The Diné – meaning ‘Navajo’ in their Athapaskan language – say the horizontal drilling and fracking could damage historic sites in the area, both inside and outside the national park, as well as contaminate the nearby groundwater.

The Diné – along with the San Juan Citizens Alliance, Wildearth Guardians, and the Natural Resources Defense Council – claim that BLM studies on fracking’s impact in the region have been shielded from the public. Without transparency, the drilling should not go on as planned, they said.

READ MORE: US geological agency calls for data sharing on fracking-induced tremors

To unleash oil or natural gas from shale or other areas, the hydraulic fracturing – or fracking – process requires blasting large volumes of highly pressurized water, sand, and other chemicals into layers of rock. Once used, toxic fracking wastewater is then either stored in deep underground wells, disposed of in open pits for evaporation, sprayed into waste fields, or used over again.

Fracking sites have proliferated immensely across the US amid the current oil and gas boom in North America. Though the costs of fracking – including groundwater contamination, heightened earthquakeactivity, exacerbation of drought conditions, and a variety of health concerns for humans and the local environment – have given many Americans pause, as they must deal with the effects while government regulators allow industry to drill like mad.

READ MORE: Living near fracking sites deteriorates health – study

The BLM’s management plan for public lands in the Four Corners region triggered a wave of resistance, as 173,000 people urged Department of Interior – the parent agency to the BLM – to “protect these unique places from oil and gas development,” according to Earth Island Journal.

“The land in the Chaco Canyon area has lots of sacred places. The corporations don’t care. They come and go and tear up the places. They do their thing and away they go—and somebody else, somewhere else is getting rich off this land, not us,” Sarah Jane White, a Diné environmental activist, told DeSmogBlog in January.

“Fracking doesn’t benefit the Native American people.”

According to The Daily Times, the BLM’s Farmington, New Mexico Field Office district manager Victoria Barr said her staff is expected to finalize the area’s resource management plan sometime later this year.

I have shovelled snow every day since January 30 of this year. I would guess I am not the only one.

Archaeologists say the rusted Winchester Model 1873 rifle may have been left at the same spot more than a century ago

An 1882 Winchester rifle which was found leaning against a juniper tree in a clutch of rocks and branches on a remote Nevada range has confounded the archaeologists who happened upon it, standing as if casually left there more than 100 years ago.

The rifle, which is remarkably well preserved, was found by a team of archaeologists in Great Basin national park in November. It will go on display this weekend at the park, the chief of interpretation, Nichole Andler, said.

How the rifle arrived at its resting place, vulnerable to the elements, a curious animal or covetous passerby, is a mystery. “We just don’t know,” Andler said, pointing out that there were no other artifacts in the immediate vicinity that could hint at who put the rifle there.

Andler said the rifle was discovered with its wooden stock partially buried, its barrel rusted and its body so browned that it “really camouflaged in with the bark and shading of the juniper tree”.

An engraving of “Model 1873” on the rifle’s side identifies it as one of the most popular guns of its era. Winchester manufactured more than 700,000 of the rifles, which Andler said were “fairly inexpensive” for the time and became known as “the gun that won the west”.

Winchester made the gun from 1873 to 1916. Until 1966, the Great Basin desert contained wilderness, ranches and mining camps; some metallic relics of the miners of Snake Valley are still scattered around the park.

Rangers, miners, settlers, ranchers or Native Americans are the likely candidates to have owned the rifle, but Andler said the owner could have been almost anyone.

“Humans have been in this valley for a very long time,” she said.

Nevertheless, park archaeologists will still search for any trace of the lost rifle in newspapers from the era, Andler said.

After its initial display, conservators will try to maintain the rifle’s good condition, which Andler attributed to the arid climate and shelter provided by the tree.

• An earlier Reuters version of this story was amended on 16 January 2015 to correct the model of gun mentioned. It is a Winchester Model 1873, not a 1773, as we first said. The headline was also changed to make it clear that an old gun had been found, not a decrepit cowboy.

As promised, here is the completed version of my post about a month ago.

Quickly done and I should wait to publish it; however I am rather pleased with the way it is coming together. I will post a finished copy later.

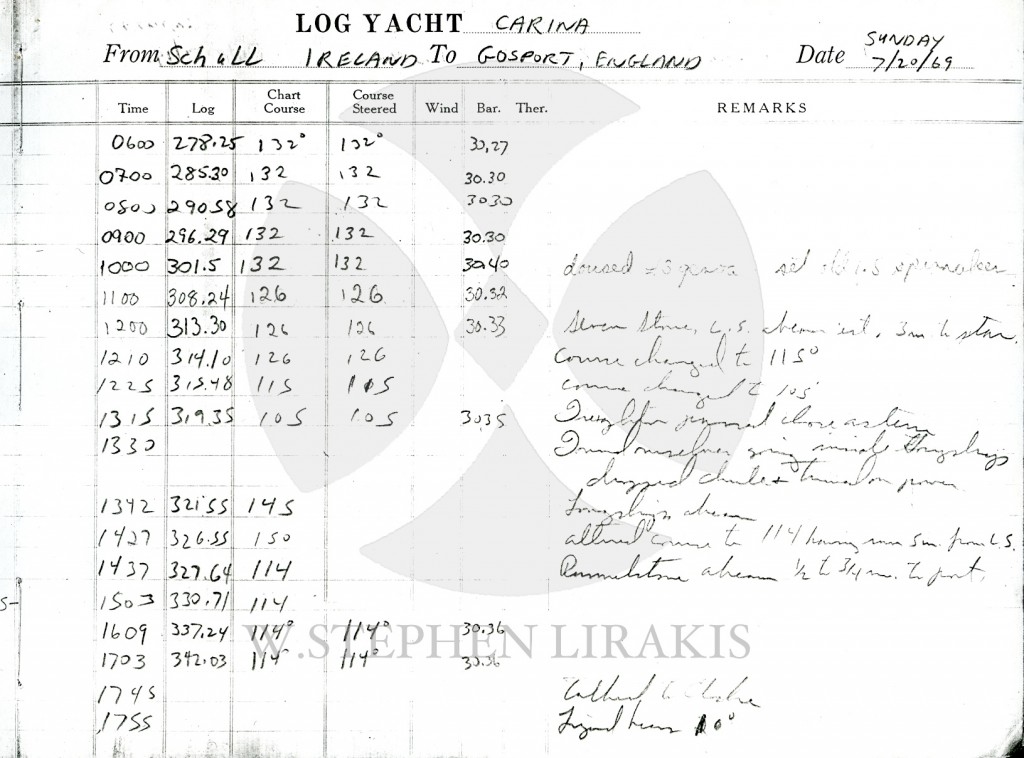

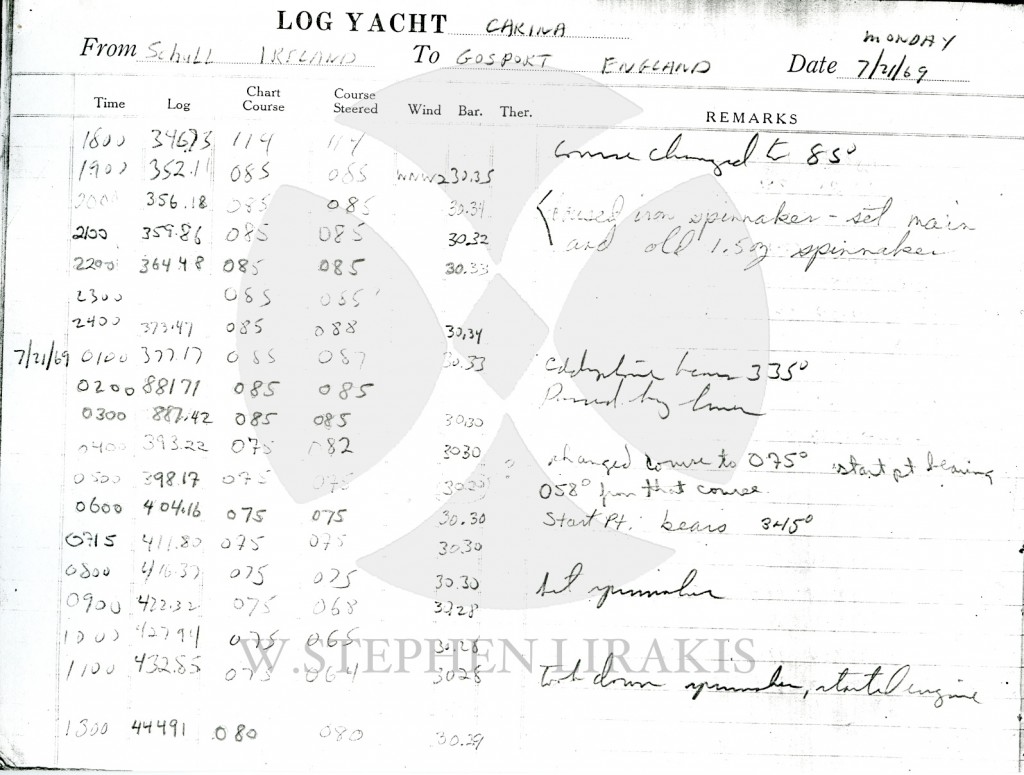

I was aboard “Carina” having finished the trans-atlantic race to Ireland, we were headed to Cowes for the Admiral’s Cup and Fastnet races. ( The US team won the Admiral’s Cup that year). I remember it being cold and foggy as we huddled around the radio at the nav station to listen the the BBC which stayed on beyond their usual sign-off time of mid-night to carry the news of the moon landing.

I will add that when I returned to the US at the end of the season; my college roommate was coming to pick me up at the airport, when another college friend passed me and asked: “how was Woodstock?”. I replied: “what was Woodstock? I was probably the only one of my generation not to have gone, much less not to be aware of the event.

What’s your favorite river? Here’s a story about mine

By John D. Sutter, CNN

updated 9:32 AM EDT, Sat July 5, 2014

Me and John Dye, of Rivers for Change, at the Golden Gate Bridge on Friday.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

Editor’s note: John D. Sutter is a columnist for CNN Opinion and creator of CNN’s Change the List project. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook or Google+. E-mail him at ctl@cnn.com. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

San Francisco (CNN) — Three weeks and about 400 miles ago, I started a trip down the “most endangered” river in the United States, California’s San Joaquin. The underloved river is born in the Sierra Nevada and snakes across one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world, California’s Central Valley.

I finished that journey — which mostly involved kayaking, but also a fair bit of walking, since the San Joaquin runs dry for about 40 miles — on Friday beneath the Golden Gate Bridge here in San Francisco.

It was a moment I’ll always remember: that behemoth, cardinal-red bridge towering overhead, clanging in the wind, the distant roar of traffic, water rushing through a 1.7-mile channel that drains about 40% of this country-sized state’s land area. The ocean tossed the kayak around like a piece of dough.

John D. Sutter

Thirty-five mph winds seared salt water to my face, and tears of joy ran down my cheeks. It was thrilling but also bittersweet. I knew that not a single drop of San Joaquin water made it to the bridge, which should be the end of the river. All of it — 100% — is diverted for a variety of human uses, mostly for farming.

As I crossed under the bridge, which separates the San Francisco Bay from the Pacific Ocean, my thoughts were as choppy as the water. But between “Don’t flip!” and “ROCK!” I looked up at the bridge and remembered a moment from my June 11 hike at the headwaters of the San Joaquin.

I could hear the river rumbling down in a valley to the left on that mountain trail, and I said something to my hiking companion, Darin McQuoid — a pro kayaker who goes careening off 80-foot waterfalls like it’s no big thing — about how, to me, the river sounded like a highway.

No, he said, it’s the opposite. Highways sound like rivers.

San Joaquin River

That’s so true. And it really clicked for me in that moment. After three weeks on the river, I was finally starting to see things from the water’s perspective.

Rivers, of course, are the original highways. The roaring traffic above on the Golden Gate reminded me of the San Joaquin in its early, healthy stretches.

But for most of us, traffic is far more familiar.

We’ve become a people disconnected from the water. We don’t know rivers. We don’t know where they start, where they’re going, when they’re full, why they’re dry. We don’t know enough to understand why — long after the Huck Finn era — they still shape our lives, they’re still worthy of our attention and unyielding respect

I hope this trip is part of a much broader effort to change that. To tilt our collective thinking toward a focus on water, and its great shepherds, the rivers.

I could go on for MANY more paragraphs about the journey — about the farmers, bird-lovers, migrant workers, fish biologists, dam operators, boat nuts and barefoot skiers I met along the way. I’ll do that at a later date as part of our Change the List project. For now, I wanted to say a heartfelt thank you to all of the readers who followed my voyage down the San Joaquin so diligently — and helpfully — on social media. Some of you sent me scientific reports about locations I was passing; others actually met me out on the river to share a piece of your story.

Two science teachers brought me a burrito beneath a bridge. One woman stood at the edge of her family farm for two hours waiting for me to pass. For all of that I am forever grateful. It’s incredible that you cared about this story so deeply. You were an essential part of it. You shaped my path.

So, I’ll say it again, since I don’t enough: Thank you.

You readers are awesome.

AND: I do have a favor to ask. I’d like to ask you to turn your gaze toward rivers, too. CNN iReport is inviting you to send in photos, videos or essays about your favorite rivers. It could be a river you saw on vacation or one in your backyard. Tell us a little bit about it and it may be featured as part of a list of “our favorite rivers.”

Here’s a page with instructions on how to do it.

I know which river I’ll pick. Certainly the San Joaquin.

Stay tuned for more reporting on America’s “most endangered” river in coming weeks, and thank you again for being such an integral part of this adventure.