The electronic monitoring of the boats racing in the America’s Cup instead of judges in boats will changes yacht racing again. The America’s Cup seems determined to alter yacht racing as we have known it. Personally I have long wondered when we would have this sort of thing. GPS has become very accurate. Judges and the boats necessary have made match racing very labor intensive and expensive. We should be using this technology in all yacht racing. It would allow very accurate guidance in a protest hearing at the least.

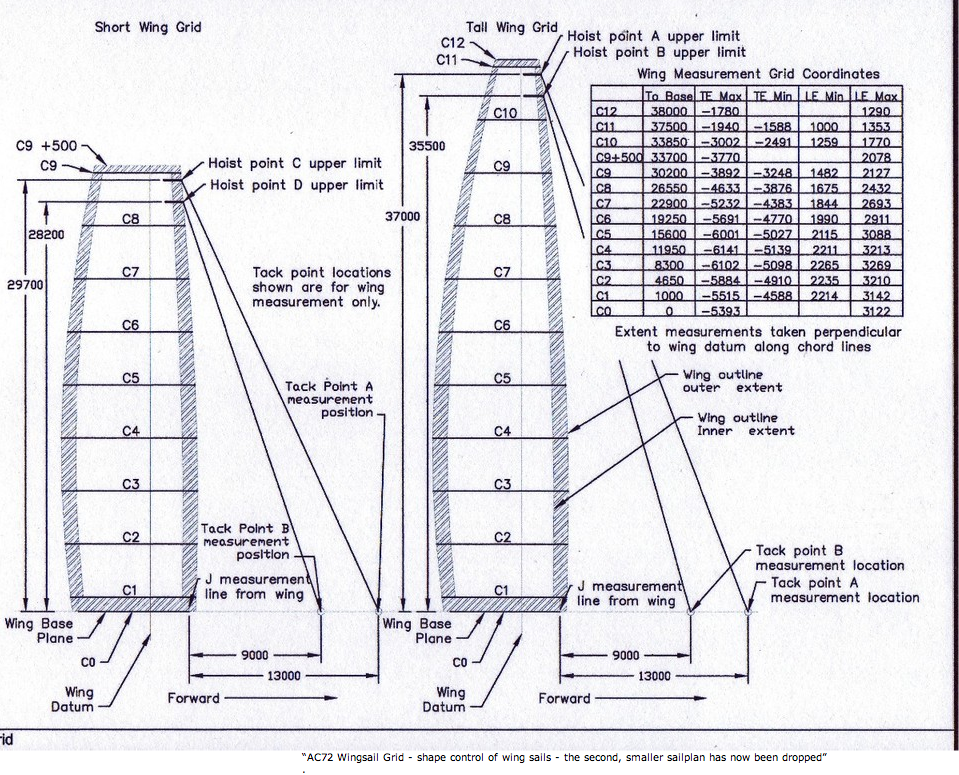

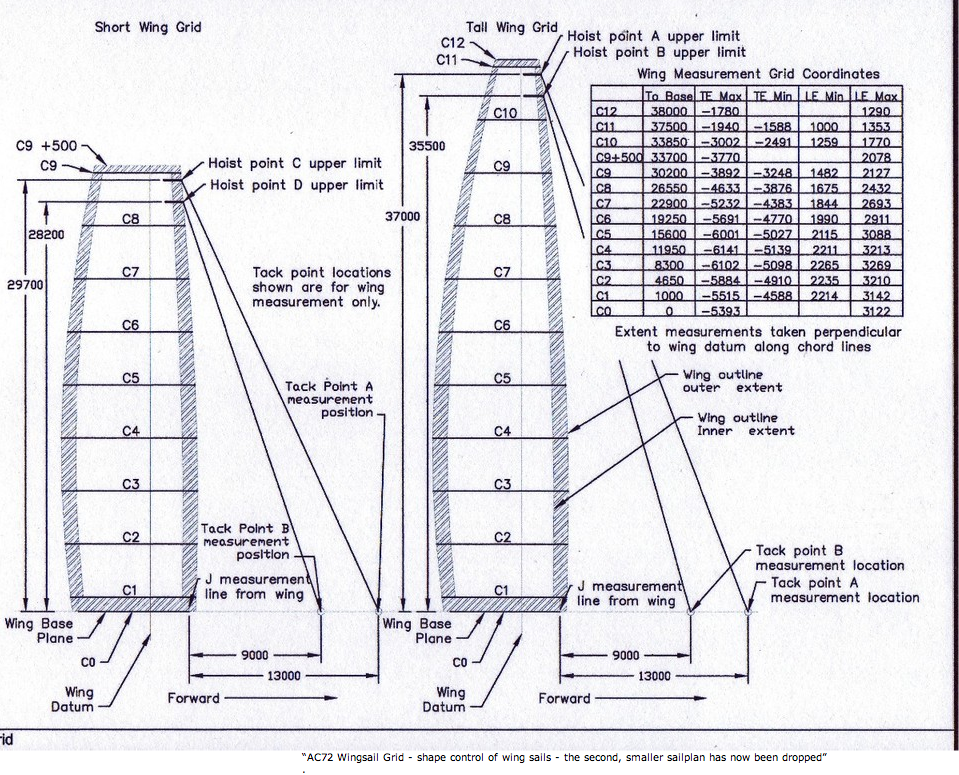

It has also been announced that the solid wings for the 72 foot boats will be only the smaller version, not several as originally planned.

This is the light side of sailing. Four Americans were killed this week in a part of the world that has become famous for Pirates.

Even for modern Navy, no easy solution to piracy

BY JEANETTE STEELE

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2011 AT 9:38 P.M.

/ USS STERETT

The 509-foot Sterett steams off Point Loma during maneuvers in 2010. The destroyer is among the Navy’s newest ships, having been commissioned in 2008.

In the vast waters around the Gulf of Aden, roughly 1 million square miles of sea, finding pirates and rescuing their victims is something even today’s sophisticated, nuclear-power Navy can’t always do.

After Tuesday’s killing of four Americans aboard their hijacked yacht off the coast of Oman, Navy officials remained silent about whether the American deaths will prompt a change in tactics. Meanwhile piracy experts say bulking up the U.S. military presence or even attacking pirate dens in Somalia isn’t necessarily the long-term answer. Any solution must change what turns people into high-seas criminals, they said.

Navy ships steaming out San Diego, including the Boxer amphibious group on Tuesday, are increasingly listing anti-piracy as one of their top deployment missions. But they are finding themselves operating in a part of the world where the brigands are not ideology-driven terrorists or warriors, but desperate youths being controlled by businessmen hungry for multimillion-dollar ransoms.

“Everybody’s going to say now we’ve got to go in there guns blazing,” said retired Rear Adm. Terry McKnight, who commanded the Navy’s anti-piracy task force when it was launched in early 2009.

“But, first of all, nobody wants to go after the pirates ashore in Somalia. And the other thing is, it’s a criminal event. You have to fall under the guidelines of international justice,” McKnight said.

“If we had a 1,000 ship Navy to go out there, we’d make a major dent in piracy … but the problem is the area is so vast you can’t be everywhere.”

Last year was the worst on record for mayhem on the seas. Pirates captured 1,181 mariners and killed eight, hijacking more than 50 ships, according to the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Maritime Bureau.

The situation is most bleak off Somalia, which accounted for 92 percent of all ship seizures in 2010.

International attention, including the Navy’s now 2-year-old Combined Task Force 151 and two European task forces, has decreased attacks in the Gulf of Aden. Navy officials said there are 34 warships, under 15 different national flags, now patrolling the gulf area.

But the pirates are pushing farther out.

Tuesday’s killings were an example of the new pattern: Somali pirates used a “mother ship,” a larger vessel they’d hijacked earlier, as a base to extend their skiff attacks northward into the Arabian Sea.

The 58-foot yacht, carrying a Marina del Rey couple and their two friends, was trailed by four Navy ships, including the San Diego-based destroyer Sterett.

Negotiation with the pirates was attempted but ultimately failed to save the Americans, who were killed by the pirates. A team of Navy SEALs raced to cover the 600 yards between the Sterett and the yacht after pirates fired a rocket-propelled grenade at the destroyer.

To Tom Wilkerson, U.S. Naval Institute chief executive, that loss of life means current anti-piracy strategy isn’t working.

Differing from McKnight, he is in the camp that says follow the pirates onto land.

“Finding pirates in the act in that area is a dice roll,” said Wilkerson, a retired two-star Marine general.

“If the U.S. and the international community are serious about reducing the piracy, they need to engage using the UN resolutions to put some kind of force ashore and remove the sanctuary.”

The Sterett is only the most recent in a string of San Diego warships drawn into pirate-fighting.

In September, a platoon of Camp Pendleton-based Marines aboard the Dubuque rescued the crew of the German cargo ship Magellan Star.

In a mission that required a White House green light, 24 force reconnaissance Marines captured 9 Somali pirates and saved the crew that was hiding in a fortified part of the ship.

Capt. Alex Martin, who led that team, said the Somalis almost instantly dropped their earlier bravado when the first Marine appeared over the bow.

“You felt like they were criminals who had been caught. It wasn’t like dealing with elements of al Qaeda in Iraq, where this is what these guys do, they believe in this,” said Martin, 28, a La Jolla High School graduate. “These were just criminals. And once they got caught, they were like, ‘Oh, God, what now?'”

The San Diego-based destroyer Howard had its pirate encounter in September 2008, when it rushed across 350 miles of ocean to aide the Faina, a Ukrainian vessel carrying military weapons.

In the end, the ship’s owners declined to risk their cargo in a raid, instead paying the pirates a $3 million ransom six months later.

And, in one of the most high-profile actions of late, Navy SEAL snipers bobbing on the back of a destroyer shot pirates holding the captain of the American cargo ship Maersk Alabama at gunpoint in April, 2009.

It was that incident, and the later 33-year sentence handed to one of the pirates by a New York court, that may have intensified the peril on the seas.

The Associated Press on Wednesday quoted Somali marauders who vowed that they will kill hostages before being captured during military raids and facing trial.

It’s not the way this business used to work, piracy experts say.

Somali pirates were known for taking hostages and holding them, alive, for ransoms that have ballooned in recent years. A common demand in 2005 was $150,000 to $200,000. Now the stakes have risen to as high as $9 million per ship, said Martin Murphy, author of the new book “Somalia, the New Barbary? Piracy and Islam in the Horn of Africa.”

If the international community promoted some other way for ordinary people to make money, that pirate bounty might not look so attractive, Murphy said, as much of it flows to the ringleaders, not the people taking the risks.

For cargo shippers, the high-stakes gamble appears to make sense for now, said Peter Chalk, RAND Corp. analyst. Using the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden cuts travel time from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean by three weeks, saving the shipping industry an estimated $2 billion a year or more.

Efforts to make ransom payments illegal have gone nowhere, Chalk said. If the United States wanted to change that, or rewrite current rules of engagement for Navy ships fighting pirates, the task would be difficult because these maritime polices are international in nature, he said.

Pleasure boaters used to be somewhat safe from Somali pirates, as they weren’t seen as rich ransom targets. That may explain why the Marina del Rey couple entered the area off Oman.

“I think here they weren’t expecting trouble because they were so far away from major concentration of attacks,” Chalk said.

As Wilkerson, the retired Marine general, said about U.S. policy toward pirates, that strategy may need to be reworked in the future.