Against the Wind

One of the Greatest Comebacks in Sports History

BY STU WOO

The winds on San Francisco Bay started kicking up in the late morning. Before long, they were blowing more than 20 miles an hour.

Jimmy Spithill and his 10 teammates put on their crash helmets and flotation vests and climbed aboard the AC72, a menacing, 13-story black catamaran capable of near-highway speeds. As a powerboat pulled them into the bay for Race 5 of the 2013 America’s Cup, Mr. Spithill shot a glance at the Golden Gate Bridge. It was shrouded in fog.

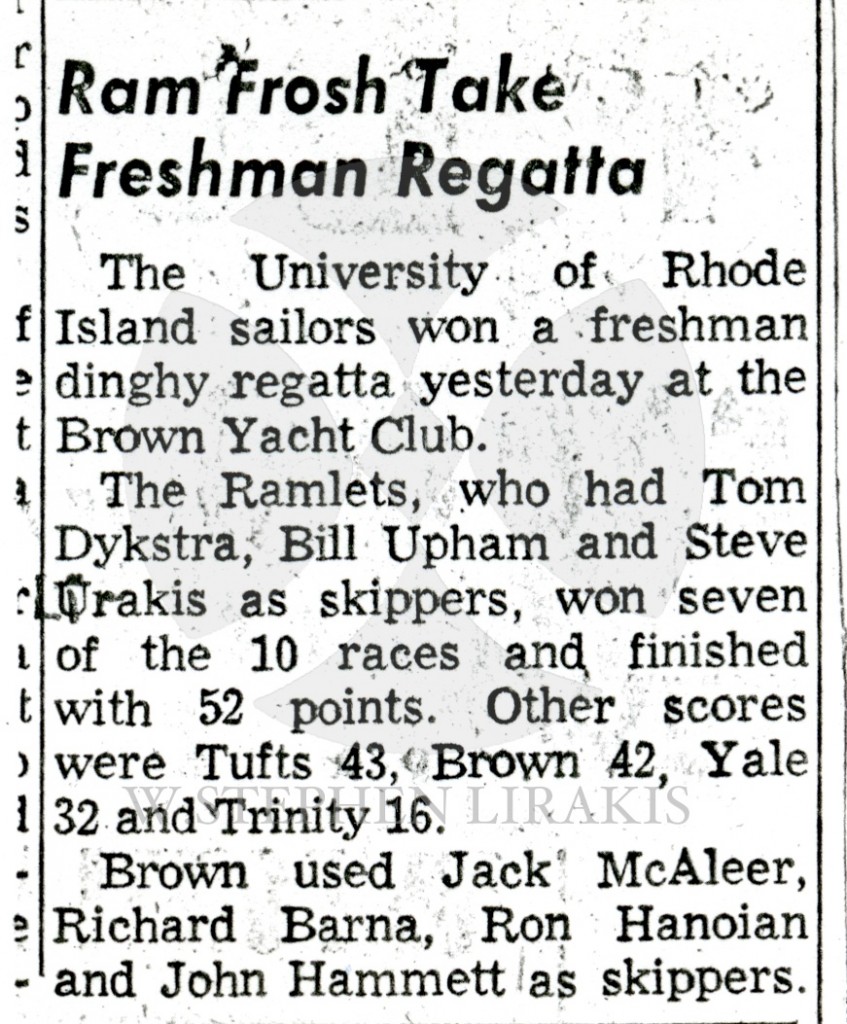

Jimmy Spithill in front of San Francisco Bay on Feb. 3, 2014. Drew Kelly for The Wall Street Journal

An unfamiliar, uncomfortable feeling was tugging at him. Mr. Spithill, skipper of Oracle Team USA, the richest and possibly most prohibitively favored team in the history of the world’s most famous yacht competition, had lost three of the first four races. Something was wrong with the way the Oracle boat was performing. Now he was facing the unthinkable: His team might lose.

The America’s Cup, first held in 1851, is believed to award the world’s oldest international sporting trophy. The contest also is one of the least professionalized. There is no permanent organization, commission or governing body. The winner gets to pick where and when the next race is held—typically every three to five years—and what type of boat is used. All that tends to make the racing rather lopsided. In most cases, the faster of the two boats in the finals wins every match—and the faster boat is usually the defending champion.

The 2013 Cup wasn’t supposed to be any different. But a competition that was expected to be humdrum turned into one of the most remarkable ever. This account of how that happened was pieced together through extensive interviews with the sailors, engineers and other team leaders.

Largely because of team owner Larry Ellison, the founder of software giant Oracle Corp. and one of the world’s richest men, Oracle had all the advantages conferred upon the incumbent, plus some.

The 11 sailors were a collection of international superstars. The engineers who designed the yacht and the programmers who built the software used to plot strategy had no peer. Oracle’s computer simulations suggested the AC72—which cost at least $10 million to build—wasn’t just the better boat in the final, it was the fastest sailboat ever to compete for the Cup, capable of 48 knots, or about 55 mph.

Mr. Spithill wasn’t sure why Emirates Team New Zealand, Oracle’s opponent in the final, had been faster so far. The prevailing theory among Oracle’s sailors was that they were just rusty. As the defending Cup champions, they hadn’t had to race in the preliminaries.

As the AC72 dropped its towline on Sept. 10 and headed for the starting line, Mr. Spithill hoped that in Race 5, the Oracle crew would get its act together.

The start of an America’s Cup race is an exercise in pinpoint execution. The two boats can’t cross the starting line until a countdown timer hits zero. On this day, both boats hit the line simultaneously.

The five legs of the racecourse sent the boats from near the Golden Gate Bridge to the downtown San Francisco waterfront and took anywhere from 20 to 40 minutes to complete, depending on wind. Through the first two legs, Oracle was in total control, building up an eight-second lead.

The upwind third leg was the one that had been keeping Mr. Spithill awake at night. Sailors have known since ancient times that sailing against the wind requires plotting a zigzag course—called tacking—steering the boat back and forth at a roughly 45-degree angle to the wind. Oracle’s aura of invincibility had crumbled on this upwind leg. If New Zealand was behind at the upwind turn, it would take the lead. If the Kiwis already had the lead, they would turn the race into a rout.

Tacking involves an elaborately choreographed routine. To initiate the turn, eight sailors crank winches resembling hand-operated bicycle pedals, powering the system that moves the sail. Two sailors pull ropes to adjust the angles of the enormous mainsail and the smaller jib. At precisely the right moment, the skipper—Mr. Spithill—spins the helm. Then all 11 sailors scurry from one hull, across a patch of trampoline-like netting, to the other side.

If everything goes right, the boat loses little speed. A small misstep or two, however, can cause the boat to bog down—or in extreme cases, to capsize.

As the upwind leg began, New Zealand headed out toward the San Francisco waterfront while Oracle vectored toward Alcatraz Island. Mr. Spithill looked over his shoulder and saw he was ahead of New Zealand by 2½ boat lengths. But the Kiwis edged closer with every turn. Within three minutes, New Zealand’s red yacht crossed in front of Oracle. Mr. Spithill had blown another lead.

By the time the boats reached the fourth leg, the gap was too large for Oracle to recover. New Zealand won by more than a minute. In racing terms, that might as well have been a week. New Zealand was now nearly halfway to the nine wins it needed to secure the Cup—and the time gap between the boats was only getting larger.

Even the Kiwis were surprised. After the race, Team New Zealand’s managing director, Grant Dalton, passed one of his sailors in the hallway and said: “I can’t believe we just won.”

As the AC72 skulked back to its berth, Mr. Spithill heard the voice of Russell Coutts, the New Zealand-born chief executive of the Oracle team, on his walkie-talkie: “Have you thought about using the postponement card?”

A postponement card is the America’s Cup equivalent of a timeout, envisioned as a way for teams to fix problems like broken equipment. By using it, Oracle would be able to delay the afternoon’s second race to the next race day, 48 hours later.

“We’re going to play it now,” Mr. Spithill told Mr. Coutts.

At the postrace news conference, the grim-faced skipper said: “We feel like we need to regroup, really take a good look at the boat.”

The following day, his team practiced in the bay and considered modifications to the boat, while the programmers ran simulations. In addition, the team’s tactician, who advises Mr. Spithill on wind, current and strategy, was replaced.

Mr. Spithill thought the break, and the small modifications they had made, might have done the trick.

The answer came quickly in Race 6. After getting blown out again on the upwind leg, Oracle lost by a margin of 47 seconds, and later that day, lost Race 7 by 66 seconds, its worst finish yet. New Zealand now needed just three more wins—and it had 12 chances to get them.

Already, the fans who gathered on the waterfront to watch the races had started cheering for the Kiwis. Unless Mr. Spithill figured out how to sail faster upwind, the affable sailor would forever be remembered as the engineer of his sport’s greatest flop.

Jimmy Spithill grew up in the tiny Australian town of Elvina Bay, just north of Sydney. He learned to sail in a leaky wooden dinghy that a neighbor had planned to throw away.

Being a sailor of modest means isn’t easy. Even as Mr. Spithill showed prodigious talent as a teenager, his parents—his father was an engineer, his mother a medical receptionist—struggled to send him to international competitions. Mr. Spithill exhibited an aggressive streak and a blue-collar mentality. Once, a week before the national high-school sailing championship, he broke his wrist playing rugby. He won the sailing contest in a cast.

In 1999, when he was 20, the Young Australia team made him the youngest skipper in America’s Cup history. The team lost, but he proved talented enough to get recruited to the U.S. team OneWorld in 2003. He lost again in preliminaries, to Mr. Ellison’s Oracle team, which went on to lose in the finals.

He returned in 2007 as helmsman for the Italian team Luna Rossa. During the semifinals of the challengers’ heats, he got his first glimpse of Mr. Ellison’s lavishly funded new Oracle team, with a budget that ran into the tens of millions. He routinely outwitted Oracle at the starting line and won the series, 5-1, before losing in the next round.

Mr. Coutts, the Oracle team’s CEO, was suitably impressed. When the Cup was over, he made Mr. Spithill one of his newest hires.

For the next Cup, team Oracle tricked out its three-hulled trimaran with a revolutionary carbon-fiber sail that looked like an upright airplane wing. Joseph Ozanne, then a 30-year-old engineer with a degree from a prestigious French aeronautics-engineering program, was responsible for designing the sail, which contained movable flaps like on an airplane.

Mr. Ozanne was in charge of a computer program, the Velocity Performance Predictor, that calculated optimal wing angles and projected speeds. But the sailors ignored his advice. “You did your job, now let us sail the boat,” Mr. Ozanne recalls being told.

Oracle Corp. founder Larry Ellison spent at least $10 million to build the AC72, the most technically sophisticated sailboat ever to compete for the America’s Cup.

After the sailors struggled for two days, Mr. Ozanne sat them down for a PowerPoint presentation. “You need to forget everything you’ve done on the conventional sail,” he said. When the sailors eventually heeded his suggestions, the boat began performing as advertised.

At the 2010 Cup, held in Valencia, Spain, Mr. Spithill led Oracle into the final. It was a cake walk, with BMW Oracle winning the first two races in the short best-of-three format. At age 30, he was the youngest winning skipper in the competition’s history.

For the 2013 Cup defense, Mr. Ellison decided to commission a new kind of boat, a decision that would turn the sport into something akin to Formula One on water. Picture two canoes, each one 72 feet long and made of carbon fiber, connected by a raft, with a 13-story wing, also made of carbon fiber, pinned to the middle. The software tycoon’s $10 million investment created a vessel that could do more than 50 mph.

The boat was so strange and powerful it was hard to handle. During training in October 2012, problems setting the sails and steering the boat caused the bows to nose-dive and the boat to pitch forward until the sail slammed into the water, leaving the sailors clinging to the yacht. The experience spooked everyone.

In May 2013, during practice for the Cup races, the Swedish team, Artemis Racing, had a similar mishap. One of the sailors got trapped underneath the boat and drowned.

Coming into the final, Mr. Spithill and his crew felt they were ready for the speed. And they had reason to be supremely confident. According to the computer, the AC72, with its skinnier hulls and drag-reducing dug-out cockpits, was superior to New Zealand’s boat.

If anyone had predicted that New Zealand would win six of the first seven races, they might have been thrown overboard. But that is exactly what had happened.

After his Race 7 drubbing, Mr. Spithill emerged from his shower to find that the team’s sailors, engineers, designers and computer scientists had started a meeting without him. All the chairs were taken.

Mr. Spithill sat on a desk and sipped a Red Bull as the 30 people took turns suggesting changes to the boat.

As mandated by America’s Cup rules, all the teams had to create boats of the same basic design—in this case a 72-foot catamaran. All of them had L-shaped boards under their hulls called “foils,” which stick down below the waterline like little feet. When the boats hit a certain speed, the hulls rise out of the water and ride on the surfboard-size foils, creating the illusion that the boats are actually flying.

Both Oracle and New Zealand had been foiling downwind. But New Zealand’s boat was getting partially up on its foils on the upwind leg, too.

Oracle had experimented with upwind foiling five weeks before the race at the insistence of Tom Slingsby, a redheaded Australian team member who had just won a sailing gold medal at the London Olympics. Mr. Slingsby had seen the Kiwis doing it in practice and the preliminary rounds, and to his eyes, they were sailing much faster than Oracle. Before the final, he had emailed Messrs. Spithill and Coutts, telling them it could be a “game changer” and they needed to try it.

For two weeks, they had—but for only a few minutes a day. Nearly every time they tried, Oracle’s hulls would fall off the foils and the bows would nose-dive into the water. There also was a bigger problem cutting into Mr. Spithill’s practice time. Cup officials were investigating a modification Oracle had made on its boat—one ultimately ruled a violation of the rules. Oracle was slapped with a two-race penalty before the competition even began.

There was little time to experiment with the new technique, and Mr. Ozanne’s software indicated Oracle would easily outsail New Zealand upwind even without foiling.

Now, with the Cup under way and New Zealand using the technique to smoke Oracle on the upwind leg, the topic was back on the table.

The engineers weren’t sure it was possible because modifications made before and during the race had created balance problems. When the AC72 was foiling, not enough of its load was borne by the rudders in the rear. That made the boat hard to control—sort of like an airplane with too much weight on its nose.

Oracle’s boat designers suggested redistributing the load, mainly by increasing the twist in the top of the sail and decreasing it down below. The shore crew worked through the night. Mr. Spithill went home to his apartment in San Francisco’s posh Marina District.

Each night, he would act out the farce of going to bed at 11—only to lie awake worrying. Before the races had begun, a confident Mr. Spithill had flirted with the idea of flying to Las Vegas during the middle of the competition to see a Floyd Mayweather Jr. boxing match. That never happened. Unable to sleep, he would eventually grab his laptop and dial up video of the losing races.

Each time, he jumped to the beginning of the upwind leg. Sailing upwind involves a trade-off between speed and distance—the tighter the angle to the wind, the shorter the total travel distance but the slower the boat moves. Mr. Ozanne’s computer program had given a target: Sail into the wind at a relatively tight angle of about 42 degrees, which would produce the optimal mix of speed and travel distance.

Looking at the video, Mr. Spithill could see that the Kiwis had come to a different conclusion. They were sailing at much wider angles to the wind—about 50 degrees, on average. They were covering more water but reaching higher speeds—more than enough to offset the greater distance traveled. Foiling appeared to be the key. Oracle’s computers hadn’t anticipated such speeds.

Nobody had expected this. Had team Oracle placed too much faith in the technology? Had its enormous budget lulled the team into overconfidence? Had Mr. Spithill gotten away from the lessons he had learned in Elvina Bay?

What especially galled him was the New Zealand team’s apparent contempt for Oracle’s approach. The managing director of the New Zealand team, Mr. Dalton, was openly disdainful of the costly, high-tech catamaran Oracle had chosen. The Kiwi boat had a similar, but more rugged, design. Dean Barker, the opposing skipper, was the son of New Zealand businessman Ray Barker, who had founded the menswear company Barkers.

Mr. Spithill didn’t relish losing the Cup to a team who could say, rightfully, that their win represented a triumph for the craft of sailing. With his team’s prospects getting dimmer by the hour, Mr. Spithill decided it was time to stop obeying the computers and start thinking like sailors.

The next morning, a scheduled off day, Oracle’s sailors made upwind foiling the focus of their practice. Rather than sailing 42 degrees off the wind, what the team called their “high and slow” mode. Mr. Slingsby suggested trying 55 degrees, which he called “low and fast.” When the boat got moving fast enough to get up on its foils, the crew made another discovery. It was able to tack more quickly—13 mph rather than 10 mph.

The mood began to lighten. But after three years of training, the America’s Cup might just come down to how well he and his crew executed a maneuver they had practiced for just one day.

In Race 8, New Zealand jumped out to an early lead. But after the boats turned upwind, Oracle was moving faster than ever. The difference was Oracle was now foiling, too.

The race was dead even until near the end of the upwind leg, when Oracle pulled off a quick turn and began heading into the path of the Kiwi yacht. In sailboat racing, the boat on “starboard tack”—when the wind is blowing from the vessel’s right side—has the right of way over a boat on the opposite tack, with the wind coming from its left side. Oracle’s turn gave it the right of way. The Kiwis would have to either slow down and turn or go behind Oracle.

New Zealand tried to turn quickly, but miscues caused the wind to catch the sail the wrong way. Its right hull lurched into the air and the giant yacht began tipping. Oracle was headed directly into the underbelly of the Kiwi yacht, which was teetering at a 45-degree angle to the water.

“Starboard!” Mr. Spithill yelled into his radio to alert race officials the Kiwis weren’t yielding the right of way. As he yanked the helm to turn away, the New Zealand boat stopped tipping and slammed back into the water. The near capsizing completely sapped its speed.

Oracle won the race by 52 seconds. The sailors pumped their fists. Despite their six-race deficit, they had clearly caught New Zealand by surprise. “We rattled them,” Mr. Spithill told his team.

Back at the Oracle base, Mr. Ozanne said he had found the flaw in the computer model. To get going fast enough upwind to get on the foils, the yacht initially had to sail at an angle that would force it to cover more water—something the computer wasn’t programmed to allow. When Mr. Ozanne input the wider angles into the software, the computer had recalculated the speed and showed the boat could sail faster that way, confirming what the sailors had found.

Six days later, early in the morning of Sept. 20, Jimmy Spithill drove through the empty streets of San Francisco to the Oracle base for what he thought could be the team’s final race.

While Oracle had figured out to how to match New Zealand’s speed upwind, it hadn’t yet mastered the technique. The Kiwis had rallied to win two of the next three races, giving them an 8-1 advantage—thanks to the two-race penalty meted out to Oracle at the beginning—then Oracle had taken a race. Still, one more loss for Oracle and it was done.

Instead of turning on the car radio, Mr. Spithill plugged in his iPod and played one of his favorite songs, Rage Against the Machine’s “Take the Power Back.”

It was another foggy afternoon and the winds were unusually light. At the start, New Zealand took an early lead. As Oracle fell behind, the team continued making mistakes. The Kiwis sailed away through the fog. Their lead grew to nearly a mile. It was, for all intents and purposes, the end.

The Kiwis had one thing going against them. Under Cup rules, the winning team had to complete the course within 40 minutes or the race would be abandoned. The winds were so light, and the pace so slow, Mr. Spithill didn’t think the Kiwis could do it. But he wasn’t sure.

At exactly 2 p.m., Mr. Spithill heard the voice of a race official in the radio. “This is the race committee,” he said. “The time limit has expired.”

The Kiwis, about three minutes from the finish, had run out of time. “It just wasn’t meant to be,” says Mr. Dalton, the Kiwi team’s managing director.

The day wasn’t over yet. About 30 minutes later, the winds had picked up and the two boats entered the starting area to try again.

The Kiwis beat Oracle at the starting line. But by the time Oracle got to the upwind leg, it had a 20-second lead. It won by a commanding 84 seconds. The score was now 8-3.

On the next day of racing, Oracle took an early lead and held on to win by 23 seconds. In the day’s second race, it did the same, winning by 37 seconds.

It was now 8-5. Oracle now was foiling faster upwind than the Kiwis. But Mr. Spithill was well aware that with one misstep, it would be over. Still, the America’s Cup would be a race after all.

In the next race, Oracle outmaneuvered New Zealand off the starting line and led wire-to-wire. The score was 8-6.

The crowds were growing. Spectators who had earlier cheered for the underdogs from New Zealand had begun to cheer for the Americans.

On Sept. 24, Oracle took an early lead in the first race that it never relinquished. In the day’s second race, it took the lead on the upwind leg and won by 54 seconds. The score was 8-8.

Now it was the turn of Mr. Dalton, the New Zealand team’s managing director, to fear the worst: that the Oracle team might pull off the greatest comeback in Cup history.

The next day, Sept. 25, was the day of the decisive 19th race. During his drive to the base, Mr. Spithill listened to Pearl Jam’s live rendition of “Immortality.”

As a powerboat towed the Oracle yacht past the Kiwi base, Oracle’s sailors waved at their opponents in what had become a daily test: How many New Zealand team members would wave back? This time, nearly all of them did.

Mr. Dalton, New Zealand’s managing director, now saw his team’s prospects as bleak. “We knew we were going to lose the last race unless we sailed a perfect race,” he said.

About 45 minutes before the start, Mr. Spithill heard a loud bang. A critical piece of the sail—a part attaching some of the flaps to the wing—had sheared off. The wing wouldn’t curve properly without it.

Two powerboats sped over and the maintenance guys climbed up onto the wing and started shooting hot glue everywhere. They finished the job about five minutes before the boat had to enter the starting area. Mr. Spithill and his tactician looked at each other and laughed.

On the San Francisco shore, the Oracle supporters were back in full force, waving American flags. Just after the boats crossed the starting line, Oracle caught a gust of wind that sent its bows submarining into the water, costing it precious seconds.

Mr. Spithill had decided to sail conservatively. He wouldn’t get tangled with the Kiwis on the downwind leg, lest they crash or capsize. His goal was to keep it close until the upwind section, where he knew his boat now was faster.

When Oracle hit that leg, it trailed New Zealand by only three seconds. On every tack, it edged closer. Not far from the San Francisco waterfront, Oracle took a lead. When the upwind leg was done, Oracle was up by 26 seconds. The race was all but over.

As Oracle approached the finish line, Mr. Spithill glanced at one of his teammates, Kyle Langford, who was working in front of him. Mr. Langford, a 24-year-old last-minute addition to the crew, was in charge of adjusting the angle of the 13-story sail with a thick rope he held in his hands. There was nothing high-tech about this job, but it was absolutely crucial. If Mr. Langford dropped the rope, the yacht would quickly lose momentum and possibly capsize.

About three minutes from the finish line, the rope slipped out of Mr. Langford’s hands. He lunged and caught a piece of it with his left hand—just barely—and held on. Mr. Spithill laughed and said, “Nice catch, mate.”

Oracle crossed the finish line 44 seconds ahead of New Zealand. The sailors hugged.

A powerboat pulled up five minutes later. On it was Oracle founder Larry Ellison. He stepped aboard the yacht and said, “Do you guys know what you just did? You just won the America’s Cup!”