I think there must be some irony here. The trend has been for narrower and narrower bow sections as designers looked to reduce wetted surface. Crews ware stacked further and further aft both upwind and down. With the success of the mini transat boat that is an ugly duckling, will the trend land in our playground? The following was written by Elaine Bunting.

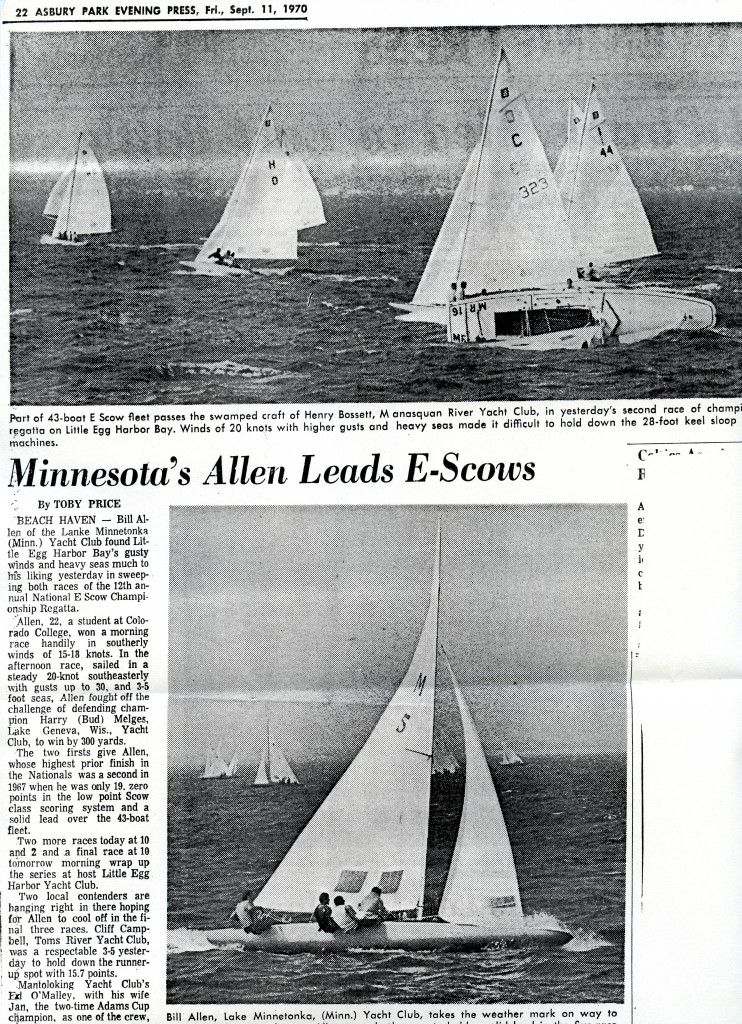

The inland lake scows have long been a favorite. I owned an “E” scow which I sailed on Narragansett Bay in the early sixties and subsequently sailed quite a lot in Barnegat Bay with Henry Bossett. That’s us capsized.

Ugly – but fast?

The latest hot trend in ocean racing design is the scow bow. But it’s ugly and it looks as if it’d be brutal upwind

I’m torn when I think about the latest trend for ocean racing, the scow bow. On the one hand, it’s a fascinating development. On the other…cripes, these new designs are ugly.

Round bowed scows have been well proven; the skimming dish designs have long been popular in the US, though less so in Europe. Yet the design principle made no major inroads into offshore design until last year, when French engineer and solo sailor David Raison won the Mini Transat in his self-designed mini 6.5m Mini Magnum/Teamwork Evolution.

This round bowed, push-me-pull-you 21-footer beat the 2nd placed prototype Mini to the finish in Brazil by 130 miles – a huge margin in such an evenly matched fleet – and recorded an average across the entire Atlantic of 6.8 knots.

He nicknamed his wide-bodied design ‘le gros porteur’, the jumbo jet, in reference to its max beam, carried as far forward as possible.

Now there is a proposal from design group Reichel/Pugh for a 90ft scow (pictured above) designed to attempt to beat the Transpac record. We’ve got a full report on this intriguing design in our May issue.

The basic principle of the scow design is to maximise hull righting moment. The beam is carried well forward which means that, when heeled, the hull lines are further outboard than with a conventional bow. This makes the scow design very powerful when reaching, obviously important on races such as the Mini Transat or the Transpac, which have a predominance of reaching conditions.

It has the added advanced advantage of large reserve buoyancy in the bow to prevent the bow from burying or nosediving when driven hard off the wind.

Put that together with a canting keel, as is the case on David Raison’s boat, and you have a potentially very powerful yacht indeed.

However there are two snags with this design.

The first is that, upwind, the rounded bow slams, even when well heeled. This means it may not be that versatile a design or particularly comfortable in all-round conditions.

And in view of what are seeing in the Volvo Ocean race, which has suffered multiple structural problems in the harsh seas of the Southern Ocean, it would be a very brave designer (and sponsor) indeed that plumped for a scow design round the world or more general racing conditions.

Secondly, let’s face it: these two new extreme scow designs are not pretty. Would you want a yacht that looked like this? I wouldn’t. If your boat was jarring as this, you’d have to win.

But since Raison’s dramatic victory, I suspect designers everywhere have been playing around with the scow idea. In classes whose rules don’t place a restriction on maximum righting moment, it’s an obvious idea to explore. If it takes off, clever minds may even find some creative ways of softening the brutal front end.