|

|

|

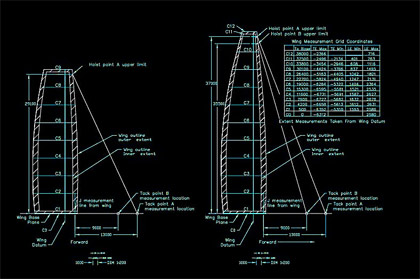

AC45 boat #1. The AC45 wing is 21.5m/70ft tall. The AC72 wing will be up to 40m/131 ft tall, about 86% larger by height and nearly double in area.

Photo:©2011 Gilles Martin-Raget/americascup.com

|

Pete Melvin, a co-author of the AC72 Class Rule, explains where technology development is likely to focus for the AC72, why the America’s Cup cats ended up with two wing sizes, and the role of the sailors in what looks like an increasingly computer-driven fast-tracked development environment:

The wing sail, brought forward from BMW Oracle Racing’s successful America’s Cup 33 challenge, might just be the area of greatest design advancement for the 34th defense of the America’s Cup in 2013. There is noticeable excitement in Pete Melvin’s voice when he discusses the possibilities of a Class Rule left wide open — and left that way for a reason.

“I think the wing and the underwater foils will be two huge areas of development. The wing needs to be a certain height and area, but how you get there, how many elements or slots or what your structure is or what your controls are, that’s up in the air. There’s been some good development on the wing in the past, but budgets have been pretty small, so we’re hoping to see development in that area.”

What sort of advancements?

“You never know, things that work better and are simpler and less expensive…. There’s a lot of promise for wings on boats, so I think this will be one of those areas that will be a good trickle down. We think there is some area for improvement in wing design, so we didn’t want to limit it to geometries that have been used in the past. We looked at a rule that’s more restrictive, such as the wings that are being used in the C-Class, but it was very difficult to write a rule around a 3D object with moving parts. Whenever we wrote a rule to limit something, we would find five ways around it. By writing very restrictive rules, you actually increase complexity and cost, so by leaving things open, things turn out to be much simpler, elegantly efficient.

“For instance, the Oracle trimaran originally had six foils,” Melvin points out. “It ended up with four — the center daggerboard and rudder were removed in the end. The wing could have been any design. But it actually ended up with a fairly simple wing, geometrically, and the appendages were as simple as you could get. If you look at the very successful racing classes around the world, such as the Open 60, they have very few rules. They’re a box rule and they’ve ended up very elegantly simple. Every year, there are incremental performance gains, but the boats don’t any cost more, it’s just different geometry and configurations. If you’re going to spend time and money on something, you might as well leave it a little bit open and let true development happen.

“The parameters of the boat we have restricted to small ranges are really the key elements: Beam, weight, sail area, waterline length. Those are the main restrictions.

“The hull shape can be anything you want. You’re allowed to have two rudders and two daggerboards, but they can be any shape you want. We’ll probably see wider variations at first, but as everyone tests designs, they’ll probably all start to look alike as we go forward, and performance will be closer. A bigger performance difference will be the actual sailors. These are new boats, so there will be differences in the learning curve.”

Ah, yes, sailors. Depending upon what you read during America’s Cup 33, what with hydraulically-canted masts, thousands of data points processed per second, and real-time heads-up display of structural loads and alarms, it’s easy to believe that software was running USA-17, not a real live crew, and that computers will win the day for AC34. But as an experienced designer of some of the most advanced multihulls in the sport, Melvin has every confidence in the ability of top sailors to figure out this new design, and he knows that sailing talent is a key ingredient in creating a fast boat in the first place, let alone winning with one.

“The best sailors, sailing either an Optimist or an AC72, the cream will always rise to the top. Some people may not be able to get their heads around a totally different concept, but if you’re a world-class sailor and you have an open mind, there’s no reason you can’t become a world-class multihull sailor as well.

“The design teams should be able to give the sailors a very good idea of how to set the boat up and sail it initially, but like any other new boat, it will have to be developed on the water. It’s impossible to model the real world in a computer, there are too many variables. It will be a development process; most of the teams will be sailing similar boats as they ramp up, like the AC45s, and I would think you’ll see most of the teams sailing other multihulls, getting some smaller boats, designing and testing smaller wings for those boats, testing some concepts and tuning up the sailing team and the design team.”

If one actually reads the Class Rule (show of hands?), it is instructive to see just how much leeway Melvin and the organizers have incorporated.

“What is interesting about the rule, and the event planning, is that organizers are leaving quite a bit up in the air so they can discard concepts that don’t work and change plans midstream. The size and the type of race course, for example, is still being debated and several ideas will likely be tried during the next year of America’s Cup World Series events.”

The practical implications of bringing wingsail technology to the America’s Cup illustrate the sort of complexities that arise in adapting to the new class rule.

“When we were sizing the wing, the end requirement was that the boat would be able to race in 5 to 30 knots. That’s a pretty wide range. But that was one of our challenges, the mandate from the media that ‘the show must go on,’ that there couldn’t be the delays we’d seen previously. The TV crews are there from around the world, so even if it’s not perfect conditions, we have to race.”

Although the demand to be able to start races on time in most wind conditions was essential for the 2013 Defense, the America’s Cup is about both advanced technology and high-intensity match racing, and even if the starting sequence is on schedule, the racing itself has to be America’s Cup-level competition. Bringing the sporting side along in the move closer to the cutting edge required some creative solutions.

|

|

|

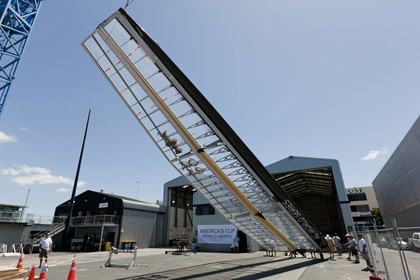

Short (32.7m/107 ft) and tall (40m/131 ft) AC72 wings.

Image: Class Rule/americascup.com

|

“That was one of the more challenging technical aspects of the rule, to come up with something that could fly a hull in five or six knots, but also race effectively in 28. We ended up with a wing that was a moderate size and some large headsails so you could vary your sail plan area by quite a bit through the range of conditions. We thought that you could still survive in 30 knots, but for anyone who’s raced around the buoys in 30 knots, it is pretty much survival at that point.”

Rather than compromise excessively on the new boat, several options for adapting wing sails to the conditions were considered, and the resulting AC72 Class now provides for two wing sizes. A tall wing can be used in lighter breeze, with the shorter wing employed in the types of higher winds that kept the old ACC boats at the dock.

“The short wing came in toward the end — the feedback we were getting was that guys would rather be able to race hard in 25 or 30 knots, so we looked at the concept of removable tips at the top of the wing, above the forestay, but the more we researched it we didn’t think it would be effective. So we thought a short wing would be preferable solution.

“It’s not something you have to have in 2012, but in 2013 you have to show up at events with a short wing,” Melvin says. “All that is a protocol issue, so I would imagine the call for a short wing would come the night before a race.

The two wing sizes each have corresponding jibs, code zeros and gennakers, which shall not be intermixed — bringing up still more questions that Melvin and his team could not answer in the four months they had to write the Class Rule.

“We thought about whether we should do more research into logistics for this rule, but we decided that the task of writing a rule in four months was big enough — to design a logistical program was asking too much. We were a pretty small team, so we knew that all the good ideas were not going to originate with our team. Once the rule was out, incredibly bright people from all these teams would start to figure it out. So the logistical team goes from 10 people to 100 plus people. We thought that was a better way to let it naturally evolve.”

In absence of hand-on experience with the AC72 in a regatta setting, how the teams and race organizers handle the big cats will indeed be a learning experience.

“Also under discussion is whether or not to take the masts out at night and how quickly teams should expect to have to change from the tall wing to the short wing,” says Melvin.

Knowledge gained from BMW Oracle’s wingsail experience is only of limited help, but Melvin believes the America’s Cup community will progress readily up the AC72 learning curve and gain confidence in how to deal with them.

|

|

|

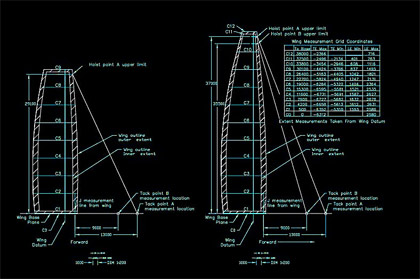

Working out ways to moor the AC45 in the Viaduct.

Photo:©2011 Gilles Martin-Raget/americascup.com

|

“BOR90 developed ways to handle the wing, which was over 200 feet tall. It was scary taking that thing up and down, because of its sheer size and all the unknowns involved, so it was very stressful. These boats are quite a bit smaller. The Stars and Stripes boat from 1988 is closer in size to the AC72, at 60’, and the owners down in Mexico keep it on a mooring. That seems to work very well most of the time, so, unless you have some extreme weather coming in, the easiest way to park the boats would be in a mooring. As the teams get more comfortable with the boats, all these perceived issues will go away.”

What did get written into the rule was a large amount of media-specific design, courtesy of Stan Honey, chair of the media development group. Melvin believes it’s a good move on the part of organizers to focus on the media presentation, to put viewers right on the trampoline of the boat as it screams across San Francisco Bay. The AC72 Rule requires provisions for no fewer than seven High Definition agile mounted cameras, three platforms for camera operators with handheld High Definition cameras, and 18 microphones for surround-sound, plus two media bays for cases, cabling, batteries, etc. This equipment is provided by the America’s Cup Regatta Management and unlike past America’s Cup’s none of it can be turned off by the competitors.

With the AC72 Rule officially adopted, these days Melvin has taken off his writing hat and replaced it with his designing hat, working with a heretofore-unnamed Cup team on their first boat. Leaving so much up in the air is great for the rule writer, but for the designer? Not so much. Some might wonder about a conflict of interest when a Class Rule author becomes a designer of that very same class, but for Melvin the design task is no easier because of it. He faces the same questions everyone else does. It’s difficult to know for sure which paths to pursue with the new boat.

“The courses have not been developed. I know with the AC45s, they’re planning some innovative courses and will do some experimentation there. It is a little bit tough, now that we’re working on designing one of these boats, we’d like to know what the course looks like, whether we’ll have reaches or not, whether you want to design the boat so it’s faster downwind or upwind, or what the right blend there is.”

In the current Protocol, the courses are due to be announced in December of 2011, but designs of the first AC72’s will already be committed at that point, with the boats far along in the construction process and nearing launch.

“There’s no time to understand what the courses are before you design your boat. I really hope they revise that and move that date closer so that when you’re designing your boat, you know. But I’m not sure if that will happen, so it’s a little bit of a guessing game. In some of the meetings, they have showed some prospective courses to some of the challengers, and they involve reaches and even downwind starts, things like that. So it’s all up for grabs right now.”

How do you proceed with a boat design amid that degree of uncertainty?

“Right now, I think you’d better be designing a boat that can do everything well, being able to switch gears and have some ideas on how you might mode your boat for different kinds of courses.

“The fun part for us is doing all the ‘what ifs’, just getting our heads around the rule as it exists, thinking of what the boat might look like and coming up with conceptual ideas, investigating different ideas.

“One neat thing about it is it’s as much a management competition as it is a sailing or design contest. If you just hire a group of designers, put them in a room and say ‘design this boat,’ you could have people going off in all sorts of directions and looking at all sorts of cool stuff, but in the end there’s a budget. And most important is time. This conceptual phase is extremely important. You realize there are some things that we think could be interesting, but we’re not going to have time to look at that. When it’s all new, there are so many things going around everyone’s heads, so many things you could look at and investigate, but you’ve really got to quickly boil those down to the things that are really promising and will give you the best return and get you across the finish line first.”

The question that will linger, if only because definitive proof will take until 2013, is what will a full-bore Louis Vuitton Cup and America’s Cup be like in a multihull class?

“I think that after the match in February [2010], there was a lot of opposition to having multihulls in the America’s Cup. But over the course of time between February and the release of the rule in October, more people had become open-minded about it. If you can change a person from being a monohull fan to multihulls, I don’t know. But I think people are willing to have an open mind, let this process play out and see what happens.”

Melvin knows how much is at stake here — including a lifelong reputation as a guru of multihulls. He also knows that many America’s Cup fans and participants alike have a way to go until they are convinced that a multihull will do justice to the event in which they are so invested. All Melvin asks is ‘Give this a chance’. |