June 25, 2014

All Possible Assistance: A Classic Escorts a Competitor to Safety

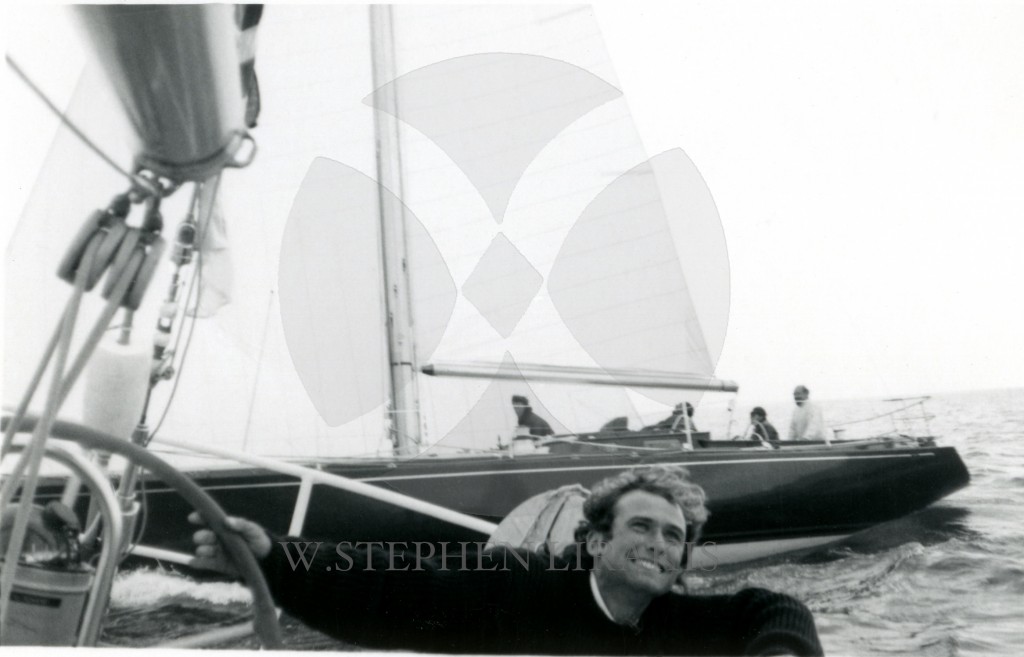

Black Watch is hard to slow down, but she had to do it during her unusual assignment in the 2014 Bermuda Race. (Daniel Forster/PPL)

By John Rousmaniere and Chris Museler

Hamilton, Bermuda, June 25. With their big fleets, Newport Bermuda Races usually have a few retirements. This year is no exception, with 10 teams dropping out mostly due to relatively small but nagging gear failures, constraints on the crew’s schedule, or (to quote one competitor) “lack of forward progress.” But also this year, a threat of serious damage led to an extraordinary response.

Halfway into the race, the bottom bearing of the rudder broke on the Taylor 41 Wandrian, a Class 3 entry hailing from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and sailed by Bill Tucker and eight other Canadian sailors. Tucker put a secondary “dam” in place to hold out the water. The crew cut out the bottom of a bailing bucket, split the remaining bucket in two, secured the two pieces around the rudder post with 4200 adhesive, finished off the dam with silicone to fill remaining the cracks and holes—and crossed their fingers. The fiberglass tube holding the post might well shake so badly that it would crack wide open.

Taylor succinctly described the danger after the boat pulled up to the RBYC pier on Wednesday morning: “Our challenge was this: if the rudder post broke, we’d have a 6-inch hole in the bottom of the boat.” All this 300 miles from the nearest shore.

Deciding to continue on to Bermuda and request assistance from another vessel, Tucker made calls over VHF radio at 12:30 p.m. EDT this past Sunday, June 22. Due to a weak connection, the transmission was not ideal, but his message was heard by Rocket Science, a Class 4 entry owned and sailed by Rick Oricchio. He then established a radio watch to check in regularly with Wandrian, and got in touch with the race’s Fleet Communications Office. Based in a room in the New York Yacht Club in Newport, and chaired by Newport Bermuda Race Communications Officer Chris McNally, the FCO maintains a continuous 24-hour watch on the race until after the last boat finishes, using radio and the race tracker.

Her details epitomize integrity. (John Rousmaniere)

As the FCO learned of Wandrian’s problems on Sunday afternoon, so did the crews of two other boats less than 5 miles away. They happened to be two classic wooden yachts designed by Sparkman & Stephens: the 68-foot 1938 yawl Black Watch, commanded by John Melvin; and the 52-foot 1930 yawl Dorade, whose owner and skipper is Matt Brooks.

Black Watch’s afterguard—Melvin, navigator Peter Rugg, and watch captains Lars Forsberg and Jamie Cummiskey—decided that their larger vessel was best qualified to stand by and escort Wandrian to Bermuda. “If the boat has to be evacuated and someone else needs to take eight or nine people aboard, we should be there,” Rugg later explained. “This is the stuff that’s important to the sport.” Added Melvin, “Dorade came over when we came over, and we decided we were the better platform to take people off.” The decision to render all possible assistance to another vessel in difficulty came easily for Melvin, who well understood Wandrian’s situation: “I sailed a little Concordia yawl for a long time and I know what it’s like to have everybody pass you and leave you alone.”

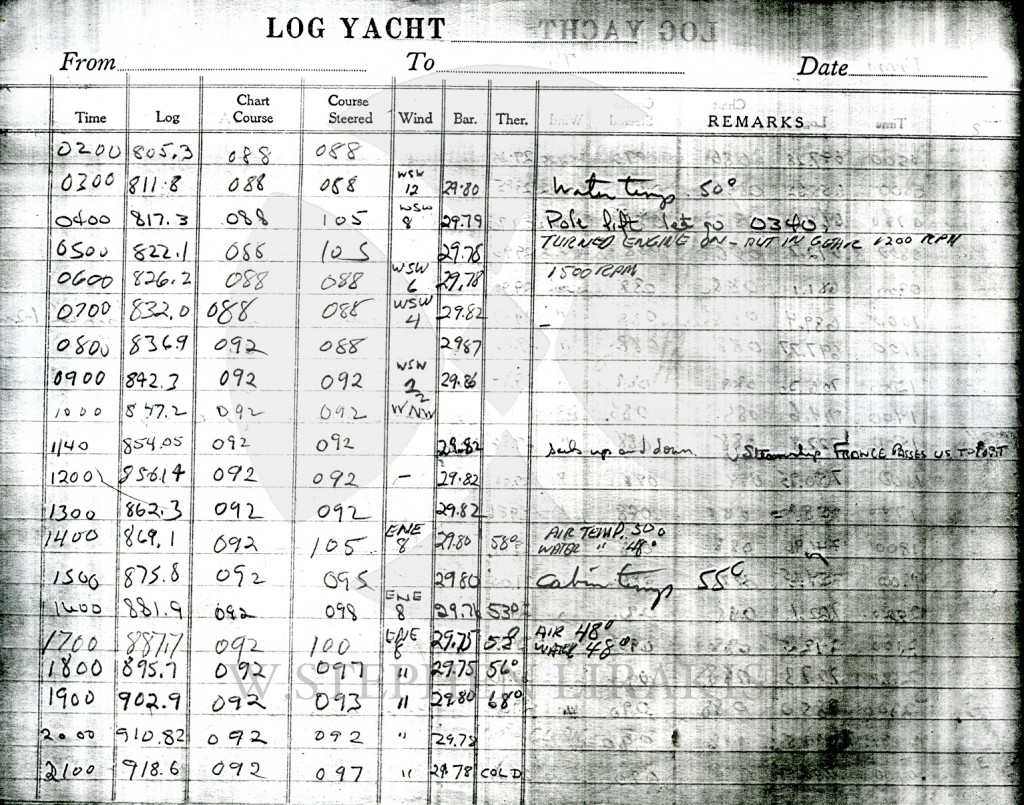

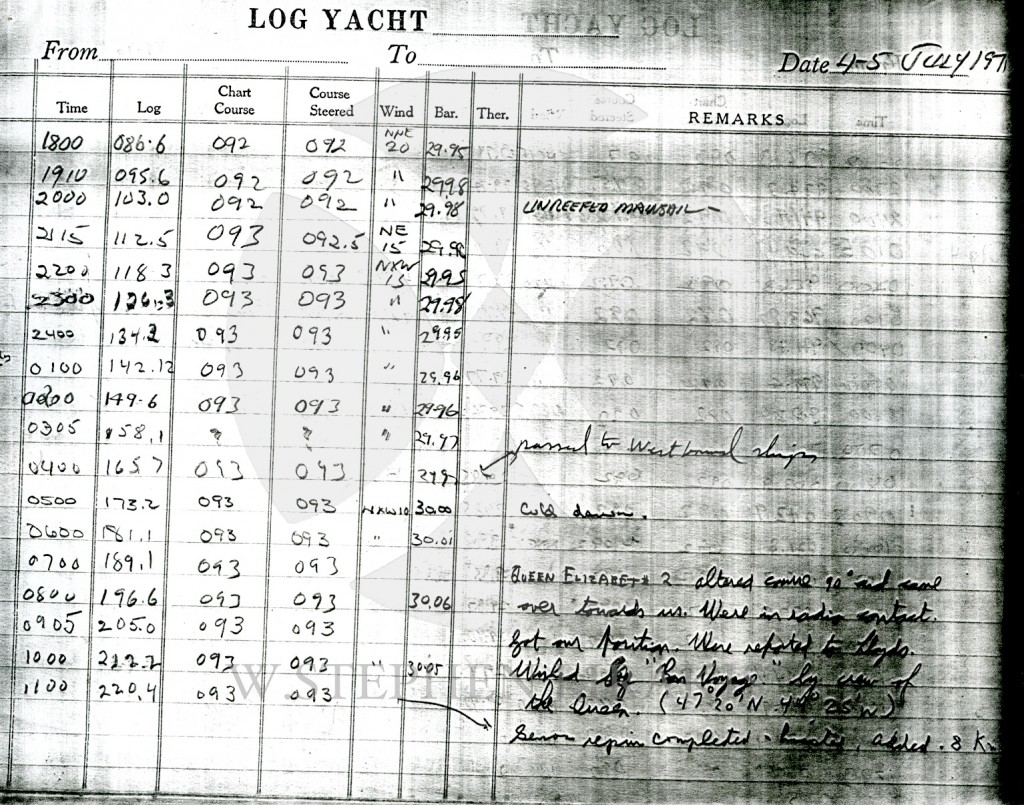

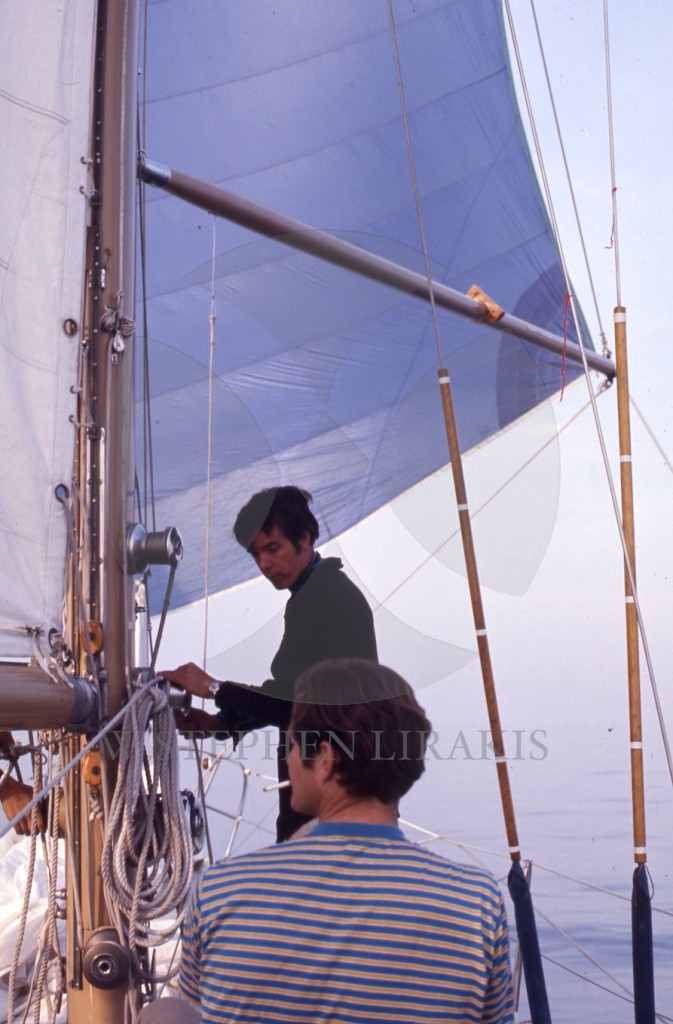

Dorade continued racing while her big cousin began the voyage in her new role as Wandrian’s shadow. The two crews engaged in hourly radio communications, with regular reports to the race Fleet Communications Office. Meanwhile, Black Watch’s sailors wrestled with an unfamiliar seamanship problem: how to sail slowly enough to shepherd a smaller boat. “In a good breeze, we can easily do 9 knots, even in rough water,” Rugg said after they reached Bermuda. “We spent a lot of time figuring out how to sail near her. We kept putting sails up and taking them down.”

Back from the sea, Wandrian is also back to normal as she waits to be hauled in Bermuda. (Chris Museler)

Experimenting with sail combinations, they settled on a full or reefed mainsail, the mizzen, and a forestaysail that could be trimmed to windward to slow the boat by heaving-to. The crew also employed the abrupt slowing maneuver called the “Crazy Ivan,” made famous by the film The Hunt for Red October. In the frequent calms, the two boats doused headsails and turned on engines. The sight of two such different sailing yachts powering side by side so far out in the ocean befuddled their competitors.

This shepherd-and-sheep relationship continued until the two boats neared St. David’s Head in the early hours of Wednesday and Black Watch sailed across the finish line at 2:22 a.m. Wednesday morning, nearly two and a half days after her crew volunteered for this remarkable assignment.

Later on Wednesday, as Wandrian was being prepared to be hauled out for repairs, Tucker paused to point to Black Watch and declare, “They were our insurance policy.”